Low-flying ground effect aircraft can deliver zero-emissions coastal transport that goes a lot further and a lot faster than electric boats – without needing FAA certification. So what happens when you add energy-dense hydrogen fuel to the equation?

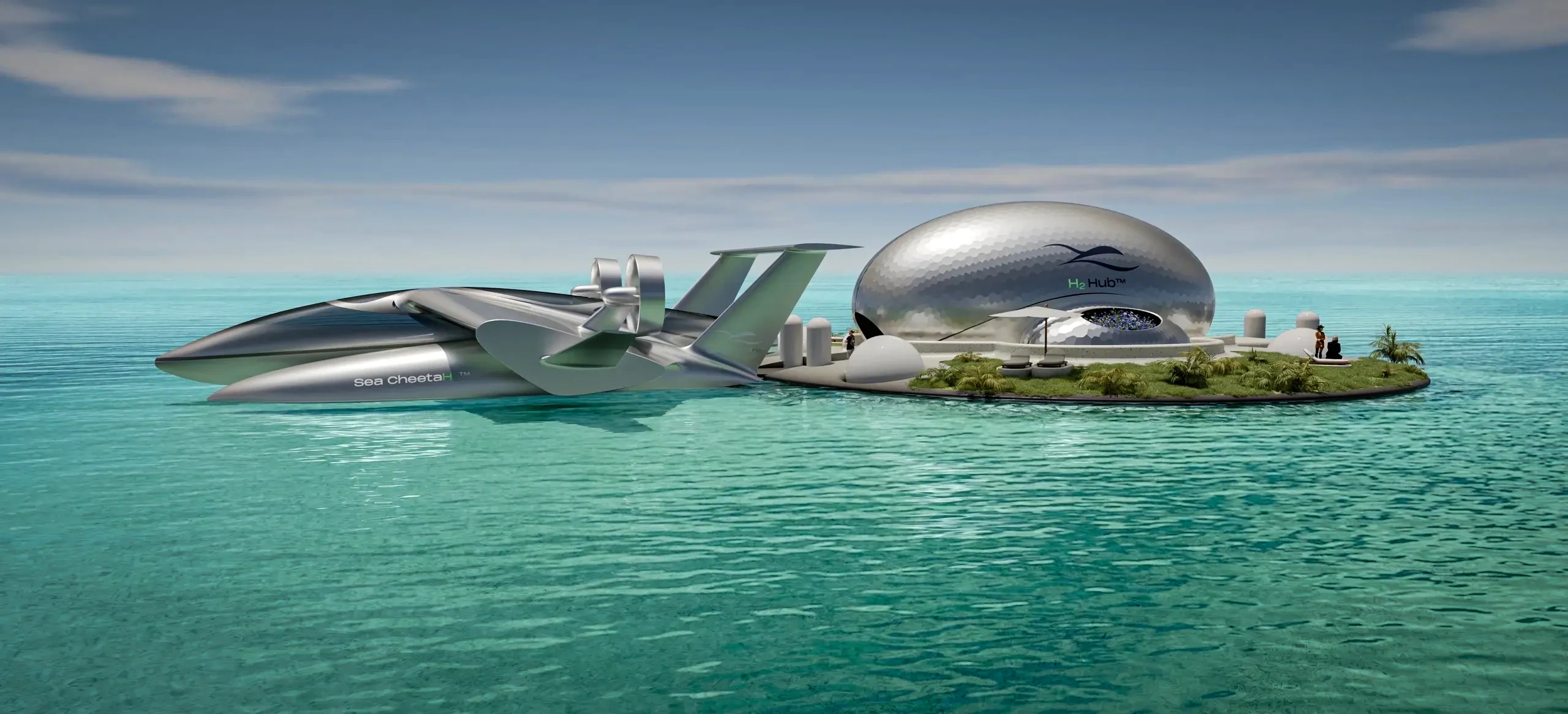

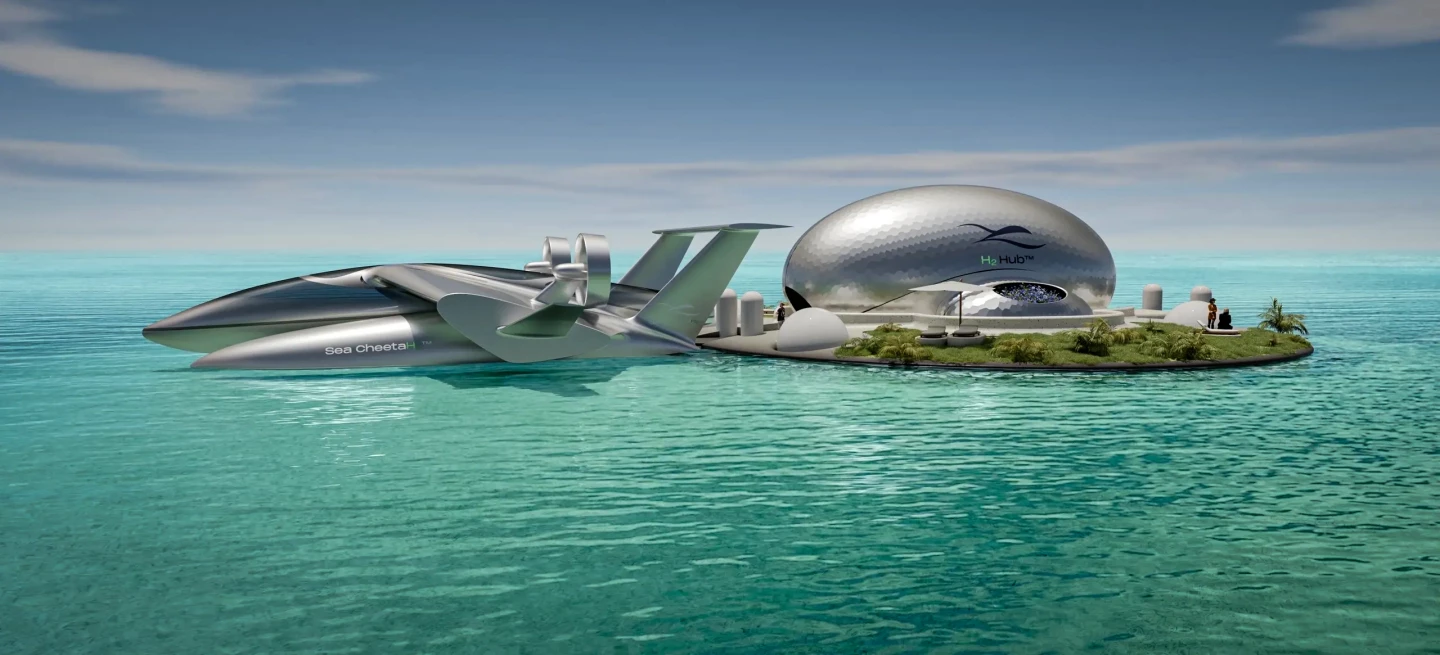

That's the question Miami startup Sea Cheetah plans to address, with a plan to develop hydrogen-fueled ocean-skimmers as well as a hydrogen generation, storage and fueling network in partnership with H3 Dynamics.

Wing-in-ground effect aircraft: Extreme efficiency and low cost

As we've seen with the fossil-fueled Airfish-8 and the battery-electric hydrofoiling Regent Viceroy Seaglider – not to mention Howard Hughes' enormous Spruce Goose "flying boat" and soviet-era ekranoplans – there are a couple of huge advantages to be found when you fly an aircraft at an extremely low altitude.

If you stay within your own wingspan of the surface, you get the usual lift effect of a wing in motion – a high-pressure zone under the wing, and a low-pressure zone over the wing where the air is forced to move faster. But with the air briefly trapped in a small space beneath the wing and the surface, it gets compressed, increasing the pressure below the wing and generating extra lift.

This is the wing-in-ground effect (WiGE), and if you manage to max it out by flying at an altitude just 5% of your wingspan, it creates so much extra lift that you can fly an incredible 2.3 times further on a given energy source.

Given the severe range restrictions batteries place on electric aircraft and boats alike, you can see how there's been renewed interest in WiGE aircraft as the world struggles to decarbonize transport.

The second key advantage, as we've discussed looking at Regent's Seaglider, is that as far as these companies can tell, they don't have to get their vehicles through the brutally expensive and time-consuming process of FAA certification to operate commercially in the United States. Indeed, the US Coast Guard has confirmed it views them as marine vessels that should fall under its own maritime regulations.

That comes with its own set of operational problems – it's gonna be extremely hard, for instance, for these things to come to a stop from high speed, or give way to other marine vessels as the current laws require. But the certification process should be vastly quicker and cheaper than going through the FAA, to the point where it fundamentally changes the economics in play.

Companies like Regent and Sea Cheetah are banking on being able to build and operate these WiGE ocean-skimmers much more cheaply than regular aircraft, in other words. So the value proposition for customers should be huge: much cheaper than air travel, much faster than a boat, and much further on a battery charge than other zero-emissions transport can take you.

Sea Cheetah wants to bring hydrogen into the equation

And so to Sea Cheetah, an early-stage Florida startup that's looking to bring hydrogen into the mix for additional range and super-fast fueling.

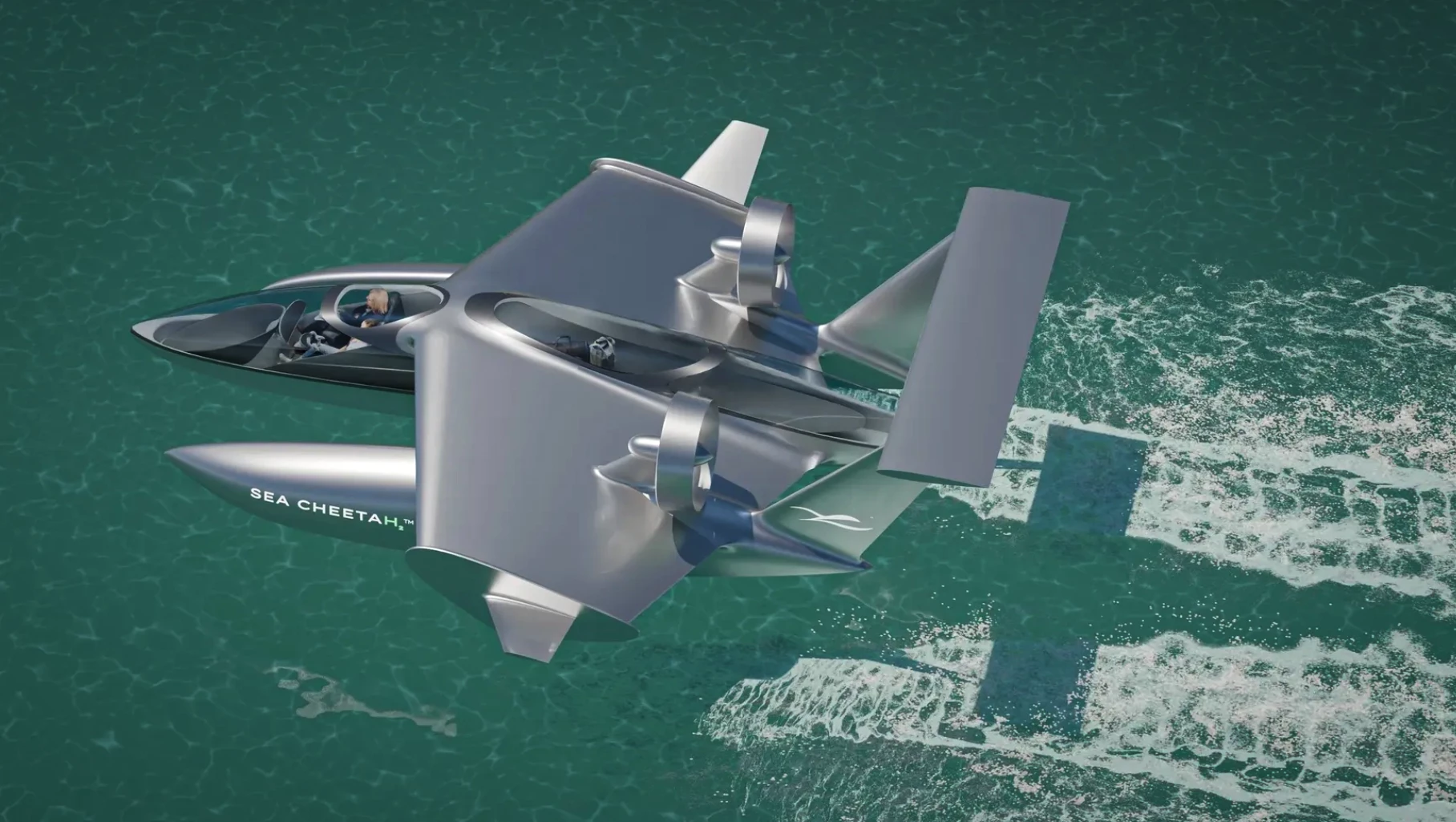

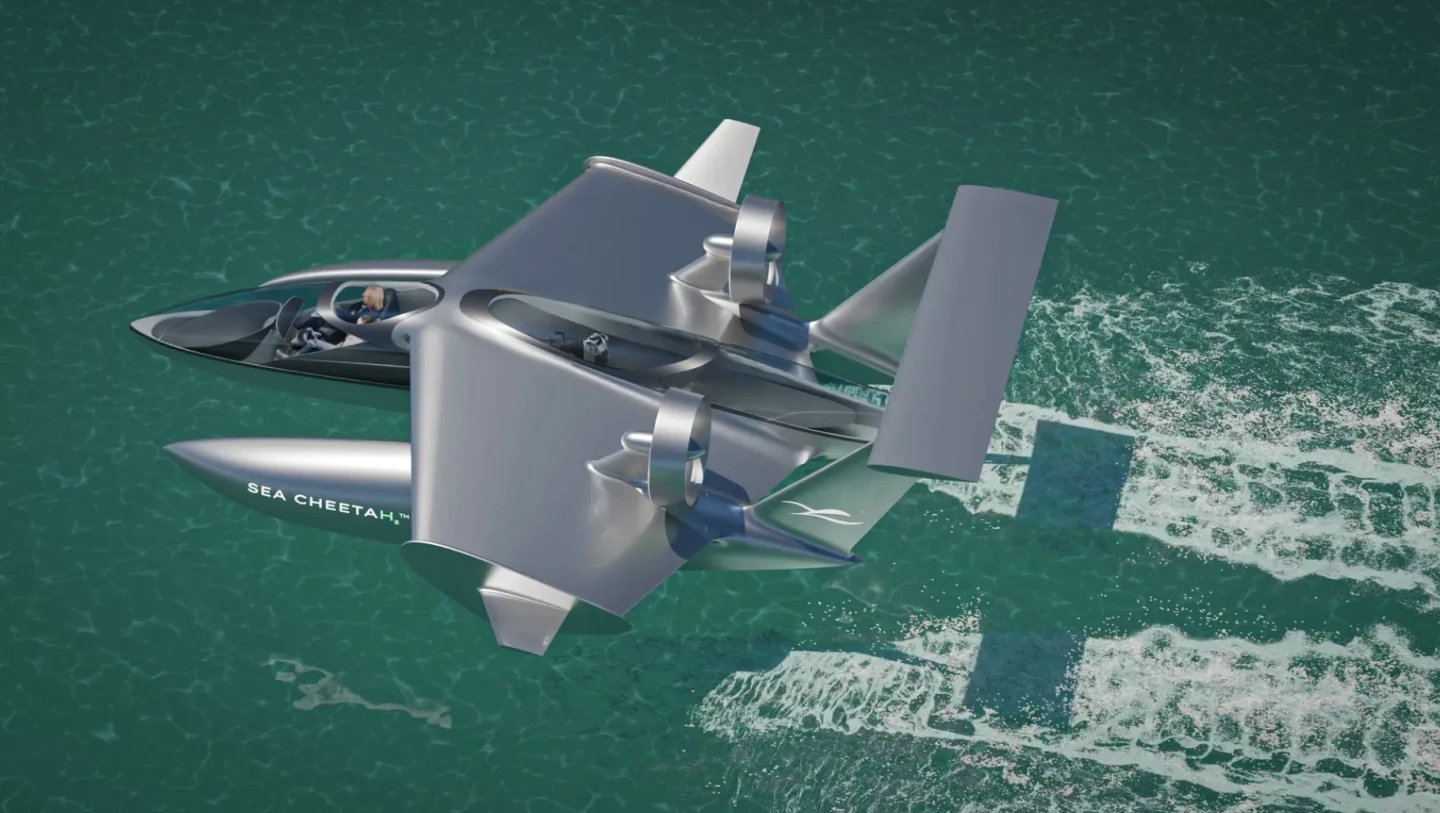

It's hard to know how seriously to take these early-stage renders; the company hasn't even got to the point of speccing out its proposed commercial offering. But the airframe here looks a lot like the Airfish-8 – it runs a fat, backswept, high-surface-area wing with upturned wingtips and twin fan propulsion blowing back under a V-supported rear wing.

Unlike the Airfish, those big fans are ducted and presumably electric, and the Sea Cheetah design has two enormous pontoons either side of the main fuselage. This, we assume, is where the high-volume, low-mass hydrogen fuel will be stored.

Several variants are planned around the same general shape, including passenger transport and cargo transport versions, as well as a fairly impractical-looking single seater. All will presumably run some kind of fly-by-wire system, which will automatically manage altitude and bank angles for safety, while allowing captains some simplified controls.

Yes, captains rather than pilots, assuming these will be classed as marine vessels rather than aircraft.

So how much better will hydrogen WiGE's be than battery-electric ones?

It's really too early even to get out the ol' back of the envelope and start wildly speculating on the effect that moving to hydrogen will have on this WiGE aircraft's range, as compared, say, with the battery-electric Regent Viceroy Seaglider, which promises to take 12 passengers for distances up to 180 miles (300 km) at a 180-mph (300-km/h) cruise speed.

For starters, we don't know whether Sea Cheetah plans to use compressed gas or cryogenic liquid hydrogen – or heck, even whether the company might be planning to burn it in combustion engines as opposed to running it through a fuel cell to extract electricity and drive an electric powertrain.

I'll say this, though – there's a whole lot of volume for fuel storage in those outrigger pontoons, so it's not unreasonable to assume that if they're full of compressed hydrogen gas, the Sea Cheetah might be able to triple the range of an equivalent-sized Seaglider – and if it were liquid hydrogen, you might be able to double that again for some super-impressive range figures.

On the other hand, if a passenger's going that far, they might well choose to take a plane instead, simply to cut down travel time; airliners cruise more than three times faster than the Viceroy.

And as hydrogen fuel becomes better understood and safety-tested in the aviation space, it could well become a relatively simple range-extension technology for a company like Regent to add to its own designs.

So Sea Cheetah may not have an enormous commercial advantage to press in head-to-head competition against this much better established rival, which has already flown prototypes and is in the process of getting a full-scale machine ready for flight tests.

So this one's a little undercooked in its current form, and these cheesy renders won't do a ton for the credibility of the companies involved. But an interesting idea to take a look at anyway, and we'll keep an eye out for updates, particularly when Sea Cheetah is ready to start slapping down some numbers to dig into.

Source: Sea Cheetah via H3 Dynamics (PDF press release)