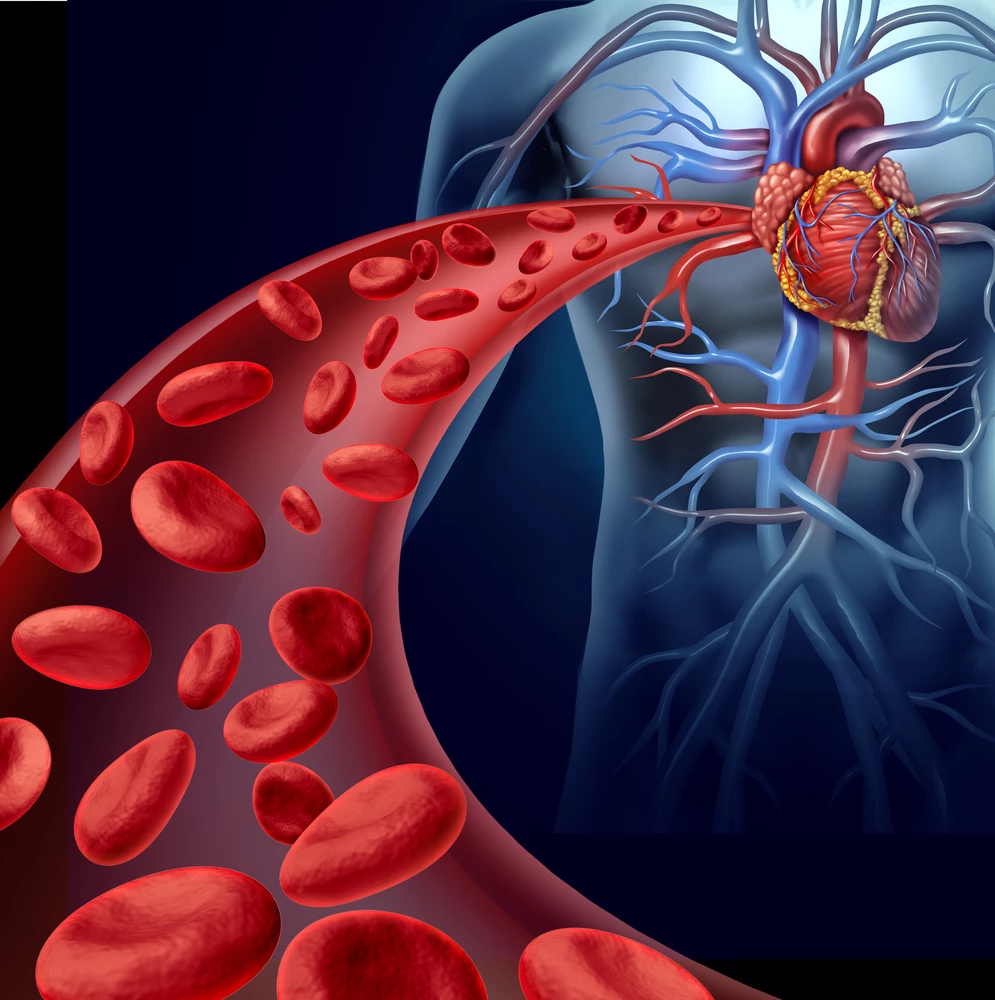

When blood clots form in the aftermath of a heart attack or stroke, medications can be deployed to break them apart, but delivery is tricky. Getting the medicine to the clot takes some guesswork and there's no guarantee it will arrive in the right dosage, with complications like hemorrhaging a real possibility. A team of Australian scientists has developed a new approach that sees the drugs carried safely inside a nanocapsule, opening up the treatment to more patients and lessening the chance of side effects.

One of the key culprits in the formation of blood clots is an enzyme called thrombin. It works by creating the cross links between clots to make them stronger. But the new approach being developed by scientists from the Baker IDI Heart and Diabetes Institute and the University of Melbourne looks to use its powers for good.

It sees an already approved clot-busting medication called urokinase (uPA) loaded into a newly-developed type of nanocapsule. As the capsule makes its way through the bloodstream, a carefully designed exterior formed with layers of peptide sequences protects its payload from breaking down.

But when it reaches the clot site, the thrombin bursts open the capsule's coating and sets the drug free, allowing it go about its clot-destroying business. And because thrombin is only heavily present in young clots, it means the approach will only target those that are freshly formed.

"If you have a clot that is old, it won't trigger the process as there is not enough thrombin," lead researcher Christoph Hagemeyer explains to Gizmag. "The intention is to give the drug as soon as possible. It could be given in a heart attack straight away, in the ambulance as soon as there are symptoms."

Tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) is another common form of blood-clot medication. We have seen the development of a similar vehicle intended to deliver tPA, which involved loading the drug into nanoparticles to improve the speed at which is destroys clots. But the Australian researchers are focusing on uPA, which they say is safer and has better potential as a drug for immediate treatment.

"We prefer it to tPA because it is safer," says Hagemeyer. "tPA has a direct effect on the brain as it can interact with neurons. It can only be given in the first three to four hours after diagnosis but not later. And as tPA is only given in hospitals and many patients don't make it to the hospital on time, they miss out on any treatment."

Hagemeyer says the approach has shown promise in early testing, describing the capsule's ability to release the drugs and dissolve clots as "very responsive." He plans to move to trials in animal models in the near future.

The research was published in the journal Advanced Materials.

Source: University of Melbourne

Update: The original version of this article incorrectly stated that tPA cannot be given for a few hours after a stroke has been diagnosed, when in fact it can only be given in the three to four hours after diagnosis. We apologize to the researchers and our readers for the error.