Researchers have homed in on a single gut microbe that acts to prevent fat gain, even with a high-fat diet. The discovery adds to the booming science of finding ways to enlist the microbes that already live in our bodies to help us improve our health.

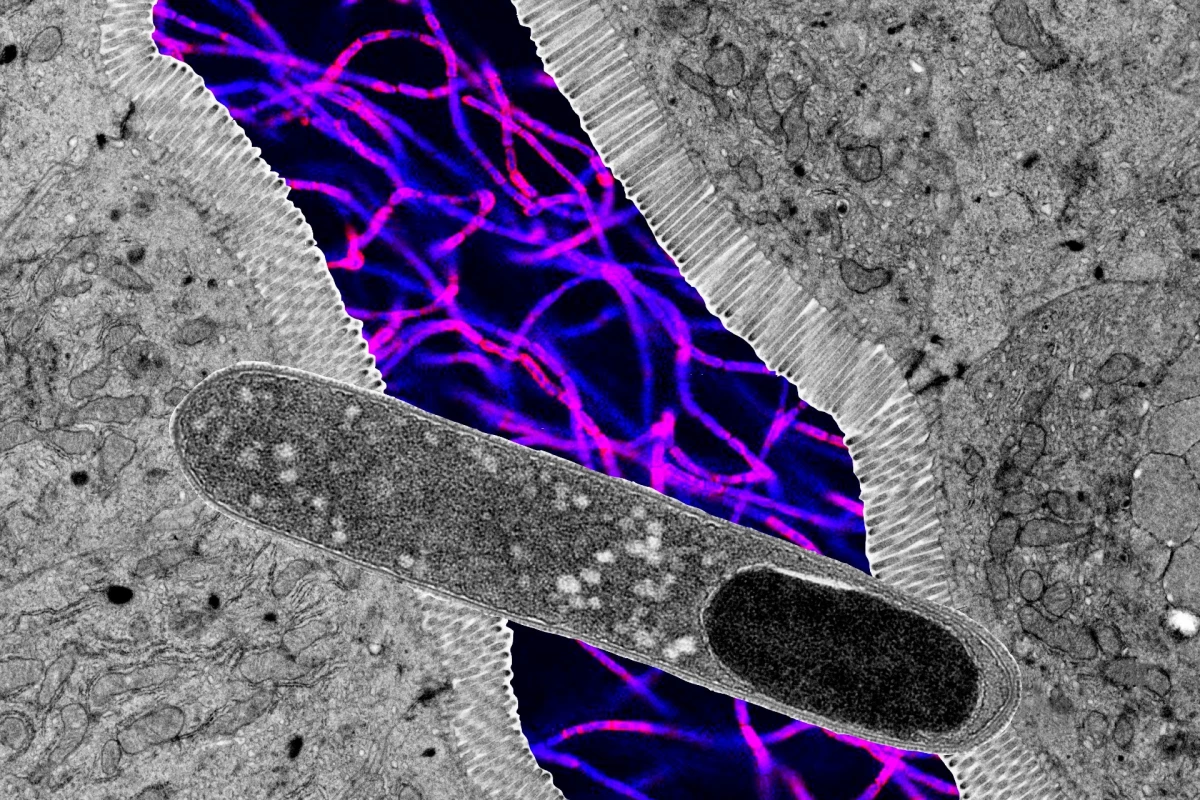

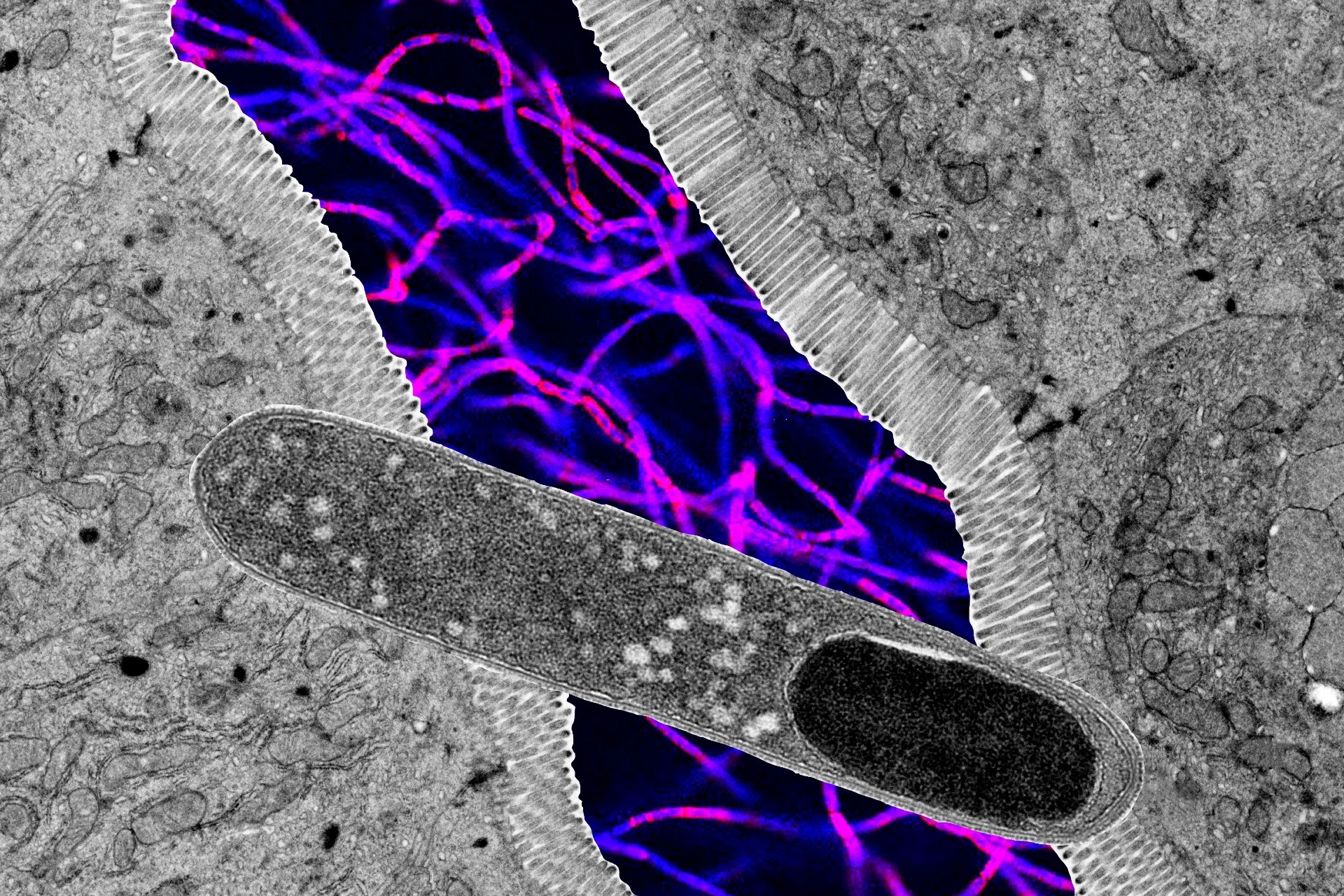

It's been known for some time that our gut microbiome – the collection of bacteria, viruses, fungi, and other microscopic critters living in our intestines – can influence weight gain or loss. But narrowing down exactly which members of this microbial community do what can take some effort to tease out. That's because microbes that live inside the body don't do well outside of it, so to test them, they often have to be processed inside airtight environments, because oxygen can often kill them. This takes time.

However, researchers at the University of Utah (U of U) say they have succeeded in whittling down about 100 bacteria suspected of fighting weight gain to just one that really does: Turicibacter.

In their study, mice that were fed a high-fat diet and were also given Turicibacter saw reduced blood sugar, lower levels of fat in the blood, and less overall weight gain compared to a control group.

"I didn’t think one microbe would have such a dramatic effect – I thought it would be a mix of three or four," says June Round, professor of microbiology and immunology at U of U Health, and senior author on the study. "So when [Kendra Klag] brought me the first experiment with Turicibacter and the mice were staying really lean, I was like, 'This is so amazing.' It's pretty exciting when you see those types of results." Klag is the first author on the study.

Fatty feedback loop

The reason why the bacteria was successful in keeping fat-fed mice thin is due to a feedback loop based on fatty molecules called ceramides. These molecules increase on a high-fat diet and, as they accumulate, they not only cause the gut to increase its absorption of dietary fat, but they push the body toward higher storage of that fat. They also spike blood sugar levels, which leads to insulin resistance. This is why elevated ceramide levels have been linked to type 2 diabetes and heart disease. In some studies, in fact, they've been shown to be better predictors of cardiovascular disease than LDL cholesterol.

Somewhat paradoxically, Turicibacter bacteria also produce lipids (fats) in the gut. But the molecules they produce actually tamp down the rise of ceramides, even in the face of high-fat consumption. Furthermore, when a high-fat diet is consumed, it drowns Turicibacter, eliminating its protective effects. In humans with obesity for example, Turicibacter levels in the gut have been found to be reduced.

Regular supplementation in the study, however, kept the levels of Turicibacter-produced fats high and the mice slim and healthy. The researchers admit that it remains to be seen if the same results carry over to humans, but point to its potential in engineering new ways to combat weight gain.

"Identifying what lipid is having this effect is going to be one of the most important future directions, both from a scientific perspective because we want to understand how it works, and from a therapeutic standpoint," says Round. "Perhaps we could use this bacterial lipid, which we know really doesn't have a lot of side effects because people have it in their guts, as a way to keep a healthy weight."

"With further investigation of individual microbes, we will be able to make microbes into medicine and find bacteria that are safe to create a consortium of different bugs that people with different diseases might be lacking," Klag adds.

The research has been published in the journal Cell Metabolism.

Source: University of Utah