Lithium. While it’s not quite “the Spice” of Dune, the silvery, reactive metal is an extraordinarily valuable means for storing electricity, meaning it’s a key tool for transitioning from climate-killing carbon-fuel consumption to a world-transforming economy and green-energy future.

Currently, about 87% of global demand for lithium is for producing rechargeable batteries for electrical grids, vehicles, and electronics including laptop computers and mobile telephones. But its other qualities are also critical, including, as Natural Resources Canada reports, enhancing “the durability, corrosion resistance, and thermal resistance of glass products used in glass-ceramic stovetops, glass containers, specialty glass, and fiberglass. Its properties improve productivity and reduce energy consumption in glassmaking.”

So, if we crave lithium so much, why do we need to attend to the black mass?

“Black mass” isn’t just the title of a heavy metal album. It’s the powdery melange of various materials from lithium-ion batteries produced during recycling. Because, as The Bulletin of Atomic Scientists reports, extracting lithium is not merely financially expensive but ecologically destructive, so the world needs to recover as much used lithium from depleted batteries as possible.

The problem is that until now, doing so has been difficult, requiring acid or energy-intense, ultra-high-temperature smelting. And that’s why a new approach from Rice University in Houston is so important. In their Joule paper “A direct electrochemical Li recovery from spent Li-ion battery cathode for high-purity lithium hydroxide feedstock,” lead author Yuge Feng and colleagues reveal how they developed a new, cleaner, and more efficient electrochemical approach for recovering lithium.

“Instead of burning or dissolving the black mass,” they write, “we essentially ‘recharge’ the cathode materials inside it, prompting them to release [lithium]. By pairing this reaction with simple processes like splitting water, we can directly produce [lithium hydroxide], a highly pure compound that can be used to make new batteries. The process only needs electricity, water, and the battery waste itself, without harsh chemicals.”

The Rice team’s method is so efficient that in experiments it yielded lithium hydroxide at over 99% purity, and was so energy efficient that it worked stably for more a thousand continuous hours, recycling more than 50 g of black mass.

So, what led to the innovative lithium recovery approach?

“We asked a basic question,” says Sibani Lisa Biswal, co-corresponding author of the study. “If charging a battery pulls lithium out of a cathode, why not use that same reaction to recycle?”

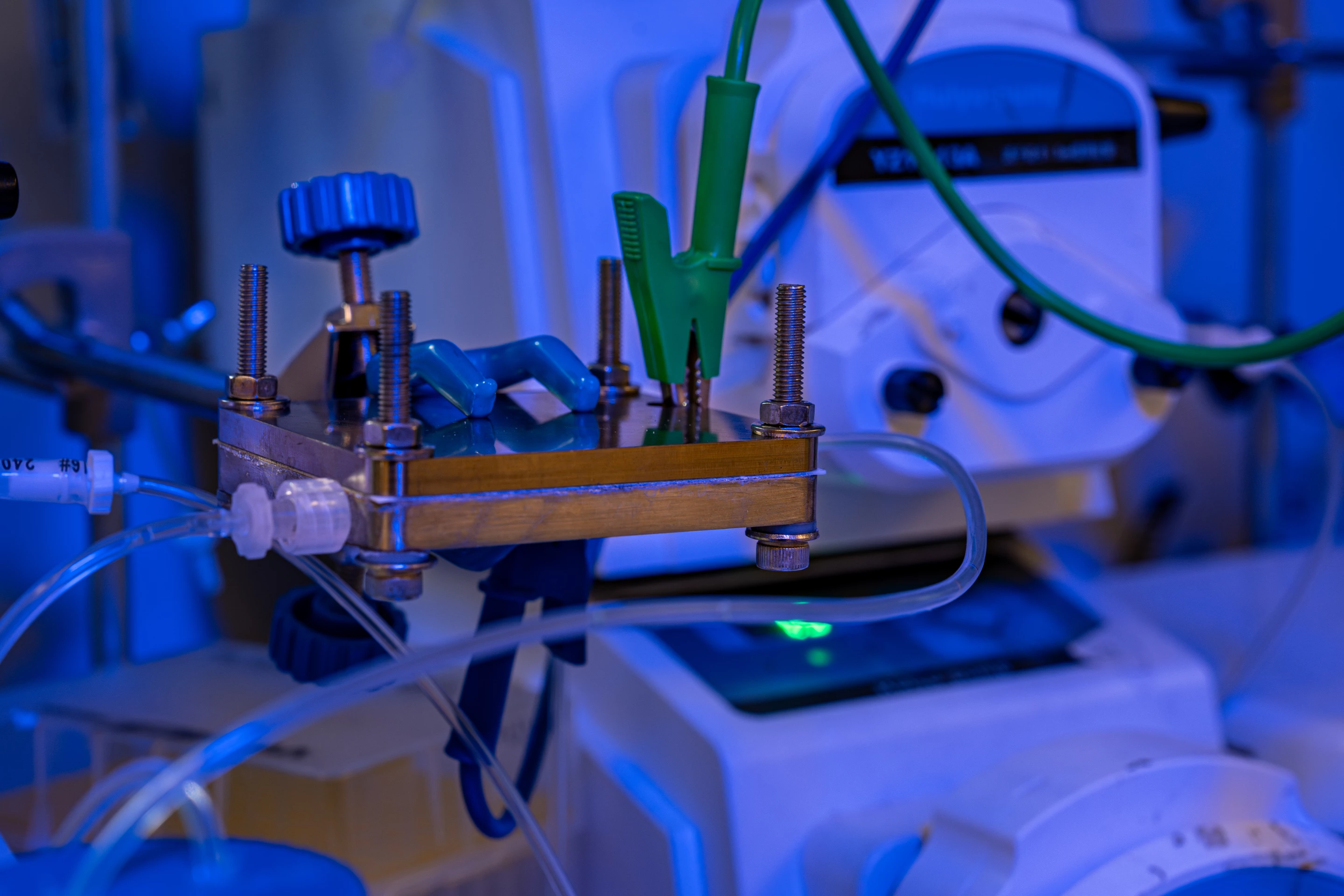

A battery works by removing lithium ions from the cathode (the electrode that accepts electrons and thus reduces the charge). During the beginning of the reaction in the Rice system, lithium ions migrate across a thin cation-exchange membrane (a layer of crosslinked polymer chains fixed with negatively charged groups) into flowing water. Then, a simple water-splitting reaction at the auxiliary electrode generates hydroxide, which combines with the lithium to produce lithium hydroxide.

“By pairing that chemistry with a compact electrochemical reactor, we can separate lithium cleanly and produce the exact salt manufacturers want,” says Biswal, chair of Rice’s Department of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering, and the William M. McCardell Professor in Chemical Engineering.

New Atlas has previously reported on fast, inexpensive direct lithium extraction that could prevent supply crises, and a super-fast robotic system for dismantling EV batteries to extract lithium, cobalt, and metal foils. The Rice approach is a further advancement because it works with lithium-iron-phosphate, lithium-manganese-oxide, nickel-manganese-cobalt, and other battery chemical variants.

As co-corresponding author Haotian Wang says, “Directly producing high-purity lithium hydroxide shortens the path back into new batteries,” which “means fewer processing steps, lower waste and a more resilient supply chain.” Wang is also an associate professor of chemical and biomolecular engineering.

“We’ve made lithium extraction cleaner and simpler” for reducing energy use and emissions, says Biswal. “Now we see the next bottleneck clearly. Tackle concentration, and you unlock even better sustainability.”

Source: Rice University