When someone overdoses on opioids, it's critically important that they receive a dose of the opioid-reversing drug naloxone as soon as possible – otherwise, death is a distinct possibility. That's where a new implant comes in, as it automatically dispenses naloxone from within the body.

Its name an acronym for "Implantable System for Opioid Safety," the iSOS implant is being developed by a team of scientists from MIT and the Harvard-affiliated Brigham and Women’s Hospital.

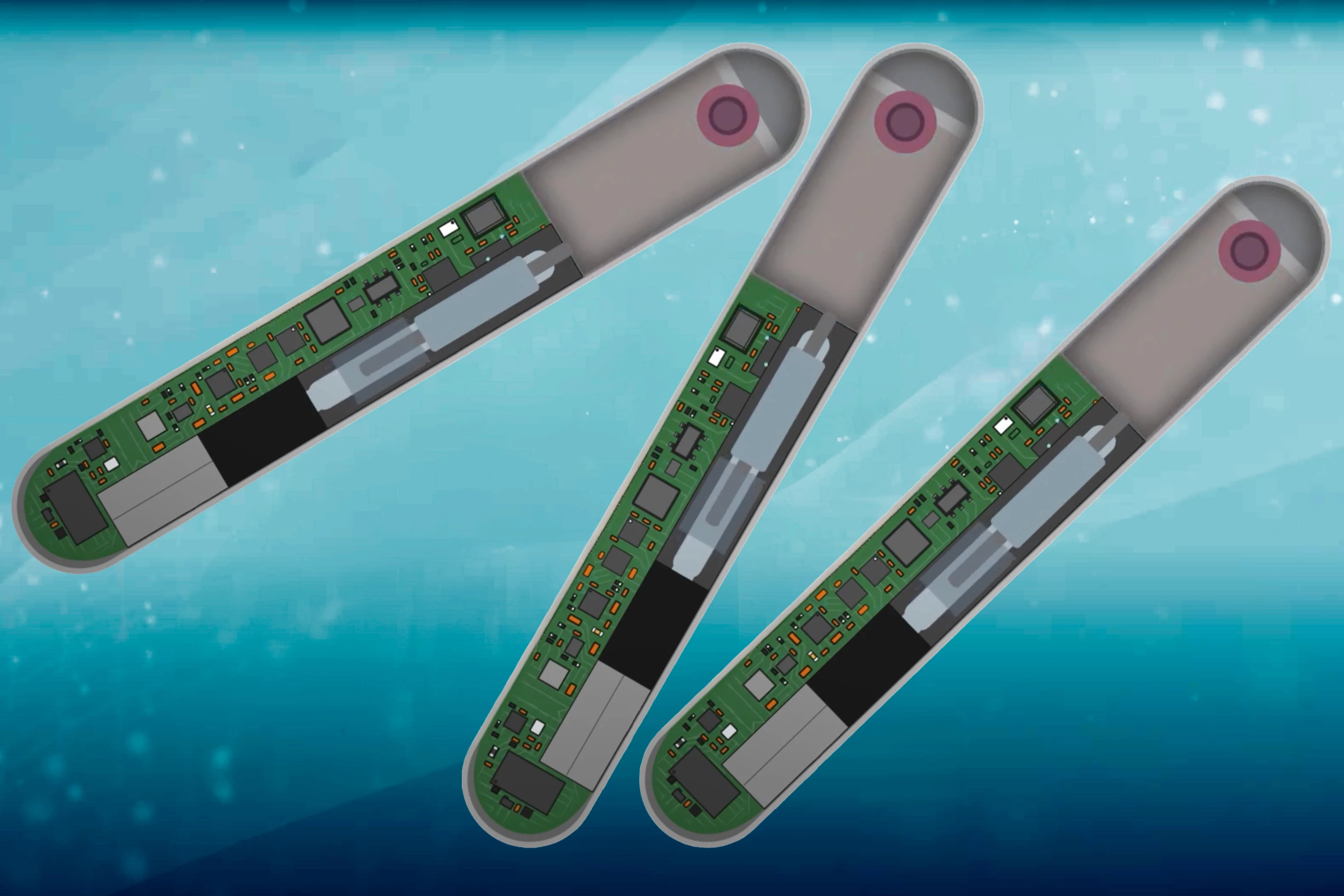

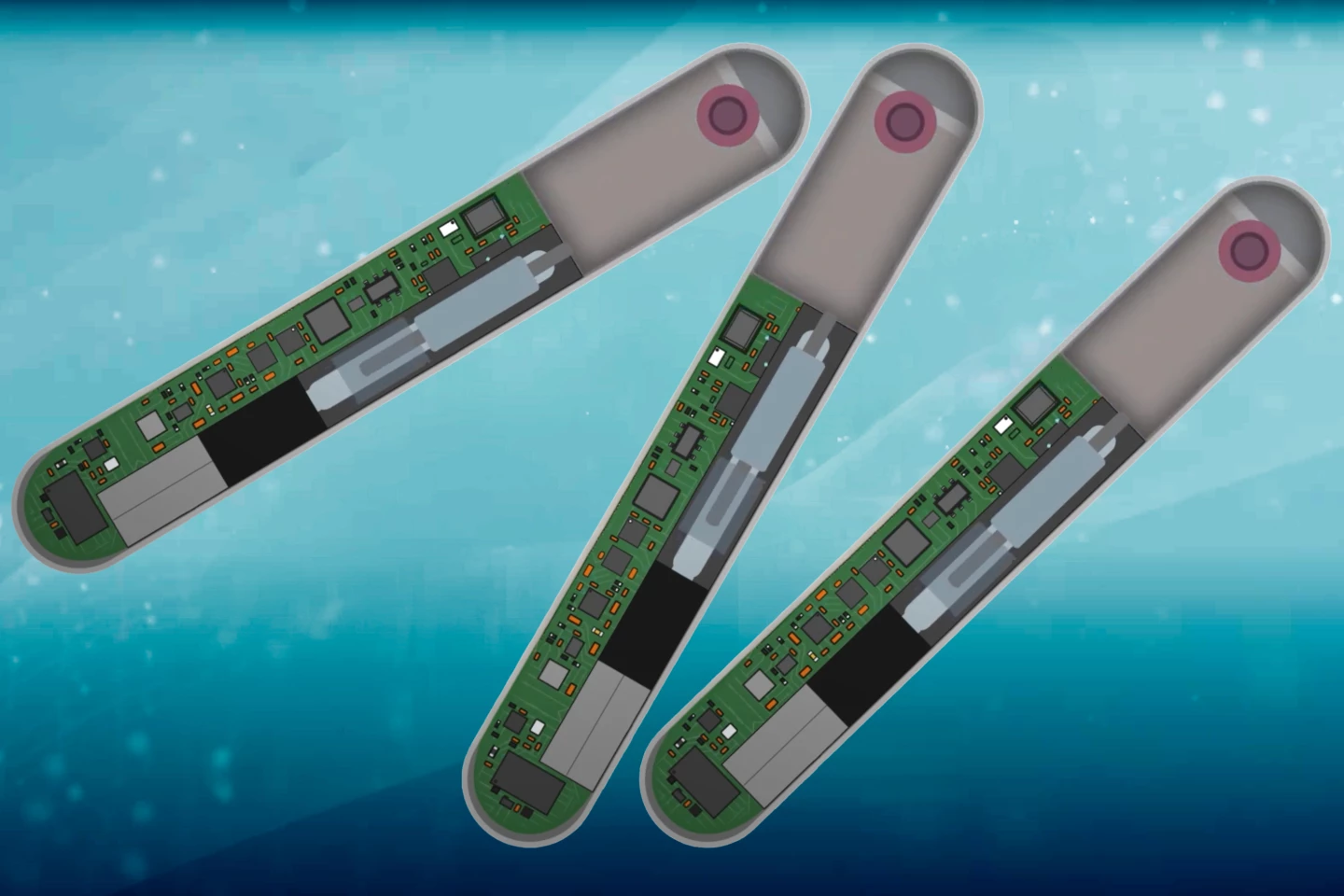

The device measures 78 mm long by 12 mm wide by 8 mm thick. It contains 10 milligrams of naloxone in an integrated reservoir, plus it incorporates electronics such as a battery, vibrator and Bluetooth module, plus multiple ECG electrodes and a suite of other sensors.

Ideally, it would be implanted right below the skin near the solar plexus. This procedure could be quickly performed in a clinic using a local anesthetic.

Once in place, the iSOS monitors the patient's body temperature, heart rate, respiratory rate and blood oxygen saturation. If these parameters change in a manner that indicates an opioid overdose has taken place, the device activates its vibrator to produce both a tactile and audible alert.

It also sends a warning to an app on the patient's smartphone. In the event of a false-positive, the patient can get the implant to "stand down" via that app. If they don't do so immediately, though, the iSOS proceeds to rapidly pump a dose of naloxone into their bloodstream. The app will also send an alert to a predetermined emergency contact.

In lab tests, the device successfully revived 96% of fentanyl-overdosed pigs within an average of 3.2 minutes. Its battery is currently good for 16 days of vital-signs monitoring, and can be wirelessly recharged as needed.

The naloxone reservoir can be refilled via a hypodermic needle inserted through the skin into a port on top of the implant. Given the fact that the drug lasts for at least 14 days at body temperature, it is envisioned that patients would simply visit a clinic once every two weeks for a battery charge and a refill.

While we have seen non-implant wearables designed for use by opioid addicts who want to survive accidental overdoses, the team behind the iSOS state that those systems typically don't deliver a sufficient naloxone dosage fast enough. Additionally, because those devices must be manually placed on the body each day, it's possible that many individuals will simply stop bothering to use them over time.

That said, one of the lead scientists does tell us that some people who could benefit from the iSOS might be resistant to having it implanted.

"While we believe many high-risk individuals who are seeking reliable, life-saving interventions will be open to adopting the iSOS device, the decision to receive an implantable device is significant and may not be universally accepted," says MIT's Assoc. Prof. Giovanni Traverso, senior author of the study. "Future work on perception and acceptability will include studies to understand better the views of both patients and healthcare providers. This research will help to address concerns, refine the device, and ensure that it meets the needs and expectations of potential users."

It is hoped that human trials will commence within three to five years, during which time a naloxone-dispensing implant being developed at Northwestern University may also progress further.

A paper on the MIT research was recently published in the journal Device.

Source: MIT