Beyond the myriad complications that come with diabetes, patients have to additionally put up with regular blood sugar testing – which involves either multiple pin pricks a day to draw blood or wearing a continuous glucose monitor patch that needs to be replaced every couple of weeks. If you're not good with needles, this can be awful.

Researchers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) might have a better way: they've developed blood glucose sensing tech that uses near-infrared light to scan tissue in your skin and accurately measure blood sugar – no needles necessary.

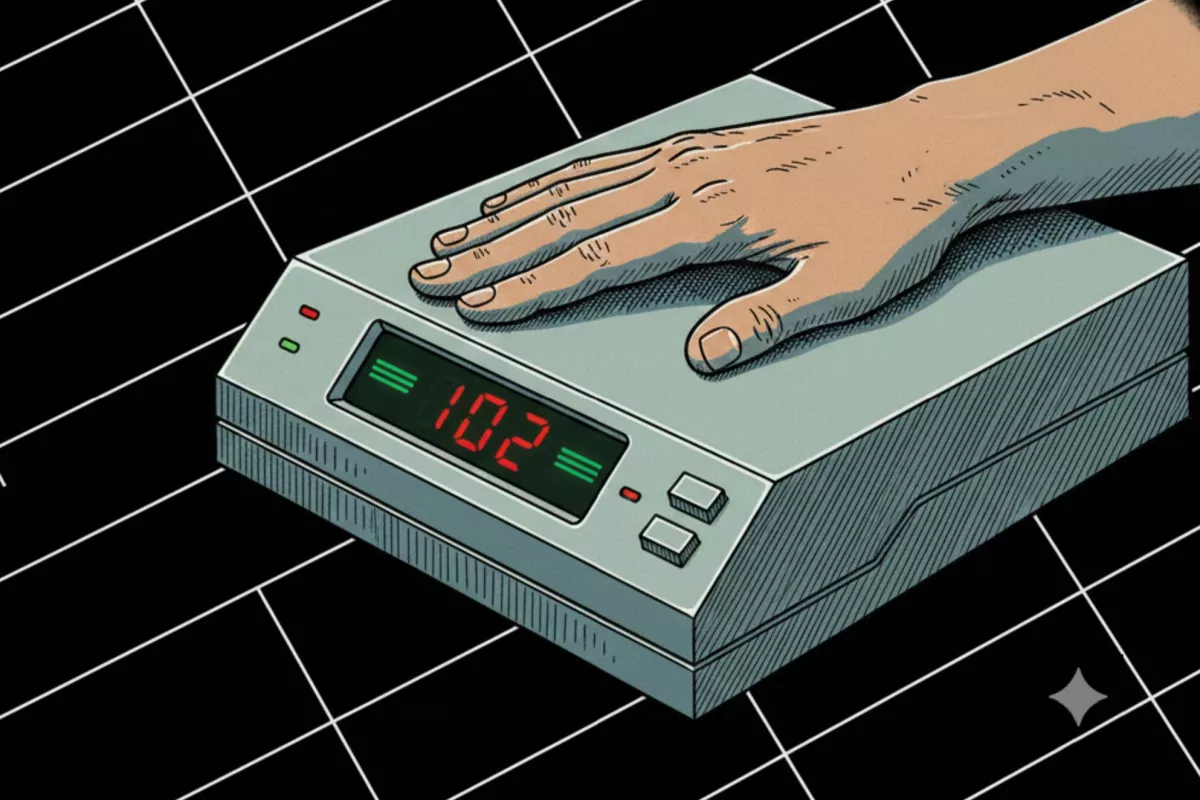

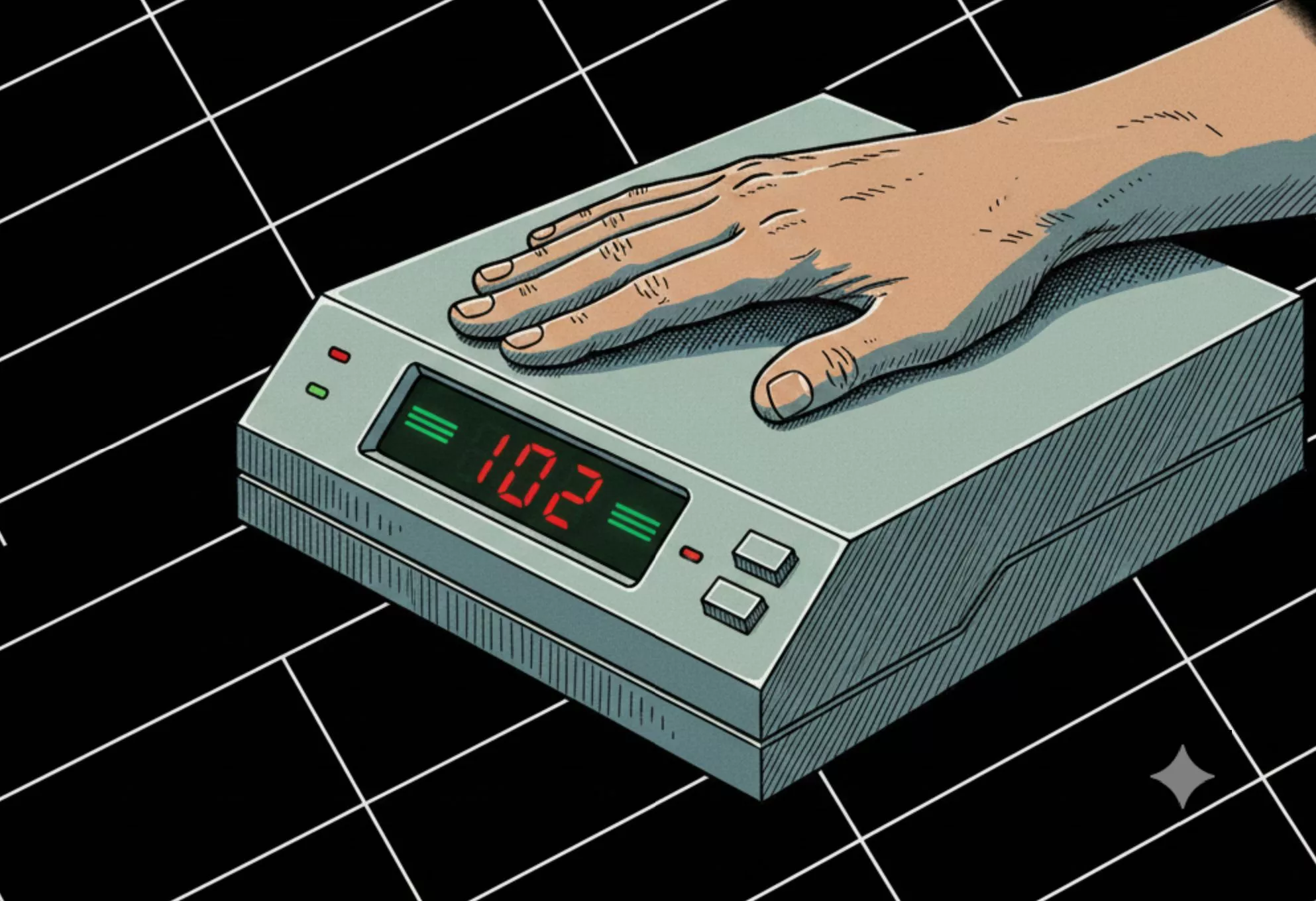

The non-invasive Raman microscopy-based system currently requires you to place your arm atop a shoebox-sized device and wait 30 seconds for a scan. Here, laser light is shone onto body tissues and the unique pattern of light that scatters back is analyzed, similar to how different materials reflect light in distinctive ways. When the laser hits molecules in your tissues or fluids, it causes them to vibrate and return light at slightly different wavelengths, revealing what's present in those molecules.

Building on their efforts to measure Raman signals from the skin that they published in 2020, the team found that shining near-infrared light onto the skin at a different angle from which they collected the resulting signal allowed them to measure just three bands of the Raman spectrum instead of the usual 1,000 or so noisy bands, to quickly and accurately determine blood glucose levels.

A clinical study involving the researchers' device, where a healthy volunteer's blood glucose readings were collected every five minutes over the course of four hours, showed that the scanner was about as accurate as two commercially available glucose monitors the participant wore.

"By refraining from acquiring the whole spectrum, which has a lot of redundant information, we go down to three bands selected from about 1,000," explained optical engineer Arianna Bresci, who led the study that's set to appear in the journal Analytical Chemistry. "With this new approach, we can change the components commonly used in Raman-based devices, and save space, time, and cost."

While the current hardware sits on a desk, the team is already perfecting a wearable prototype that's about the size of a cellphone. It's already being tested in a clinical study, and will later be put through its paces in a larger trial including people with diabetes. The researchers hope to subsequently shrink the scanning tech enough to fit into a watch-sized gadget.

This isn't the first attempt to ditch the needle for blood sugar testing: last year, we saw a non-invasive ECG device on a chest strap weighing just half an ounce (15 g) that predicted glucose levels from ECG data. It appears to still be a year out from becoming commercially available. Hopefully we'll see these two solutions and more on the market for less stressful sugar monitoring soon enough.

Source: MIT News