2023 is not a good year to be running a submarine company, but we caught up with Patrick Lahey, CEO and co-founder of Florida's Triton Submarines, for a three-part chat about a remarkable career with highlights as low as a human being can possibly go.

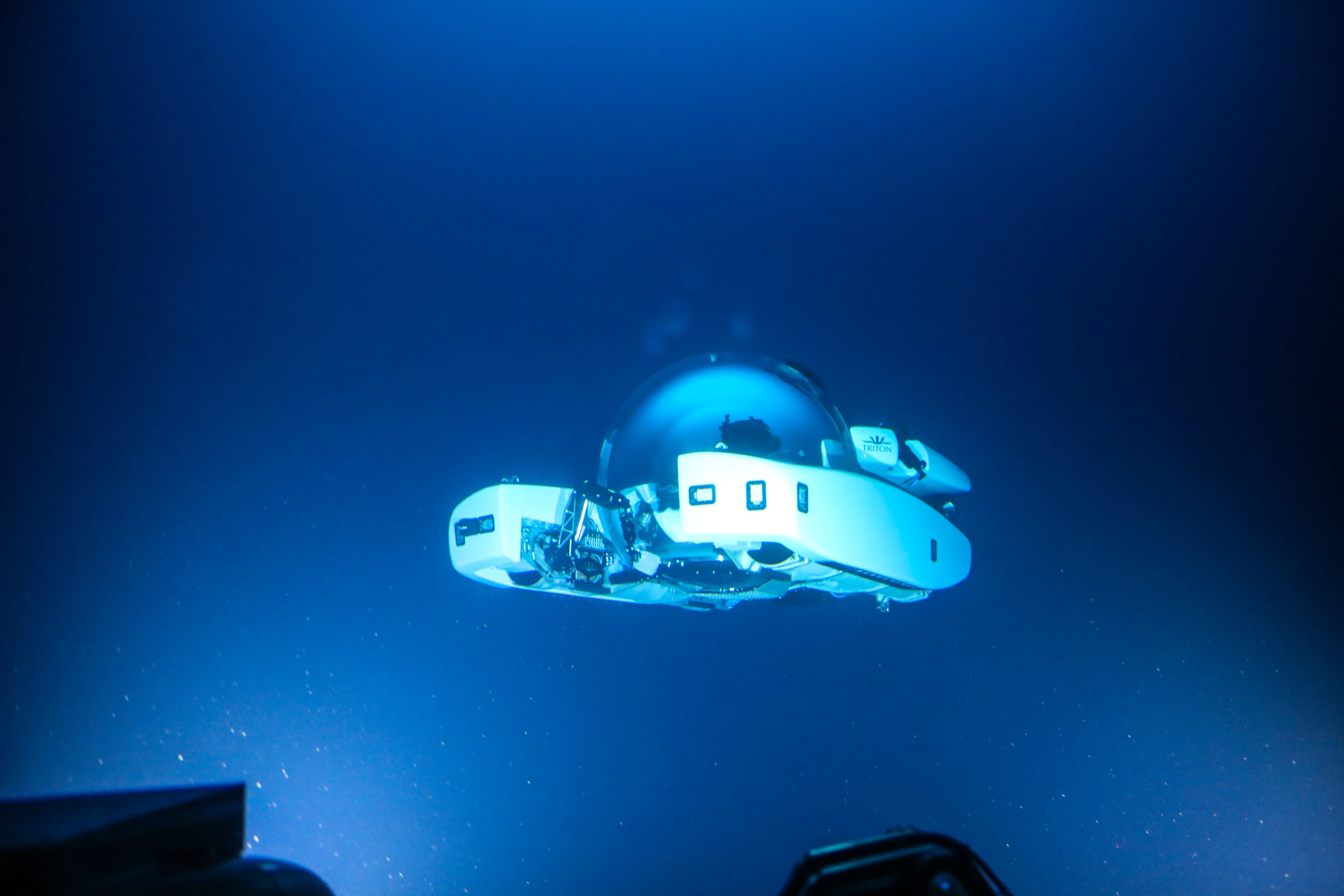

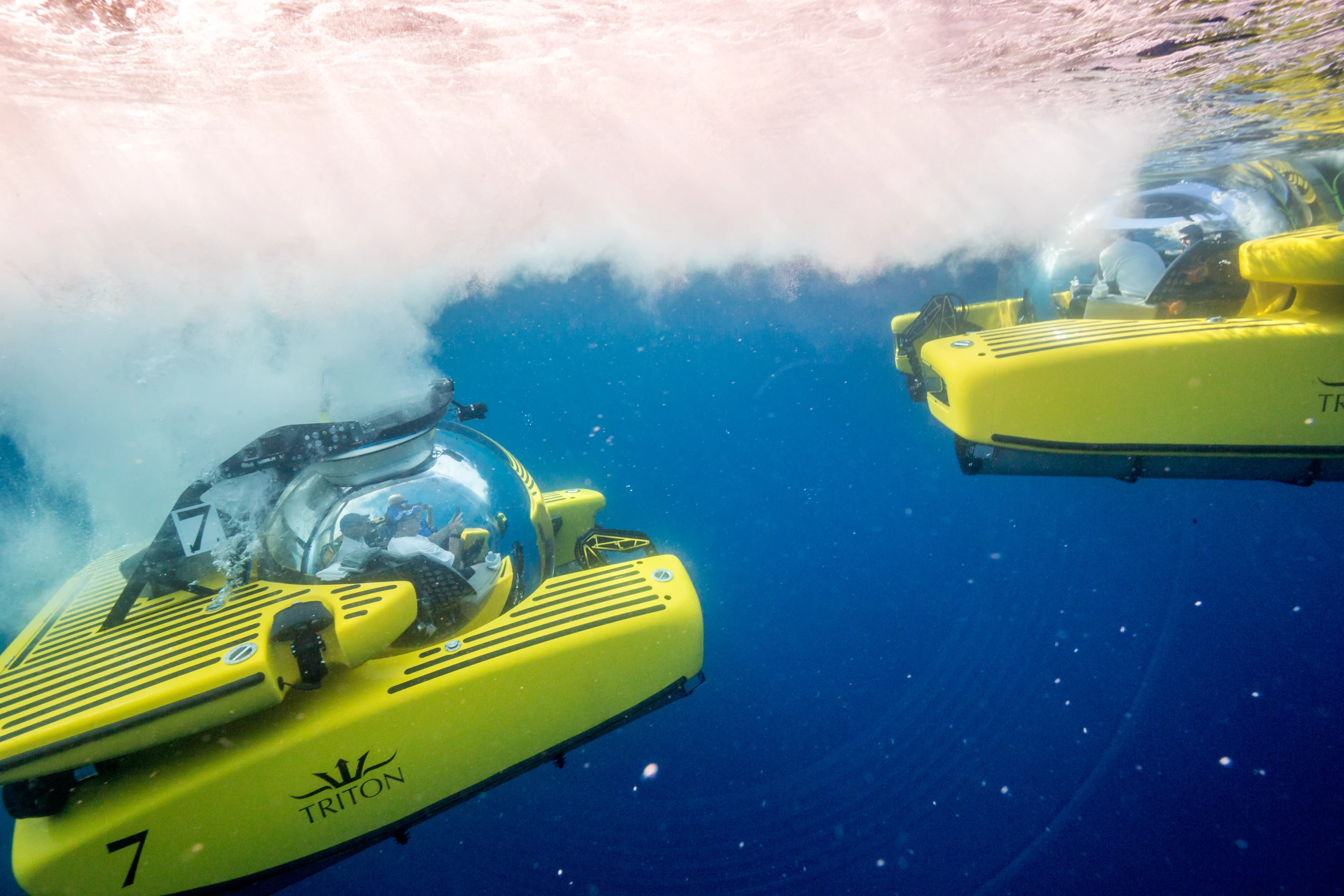

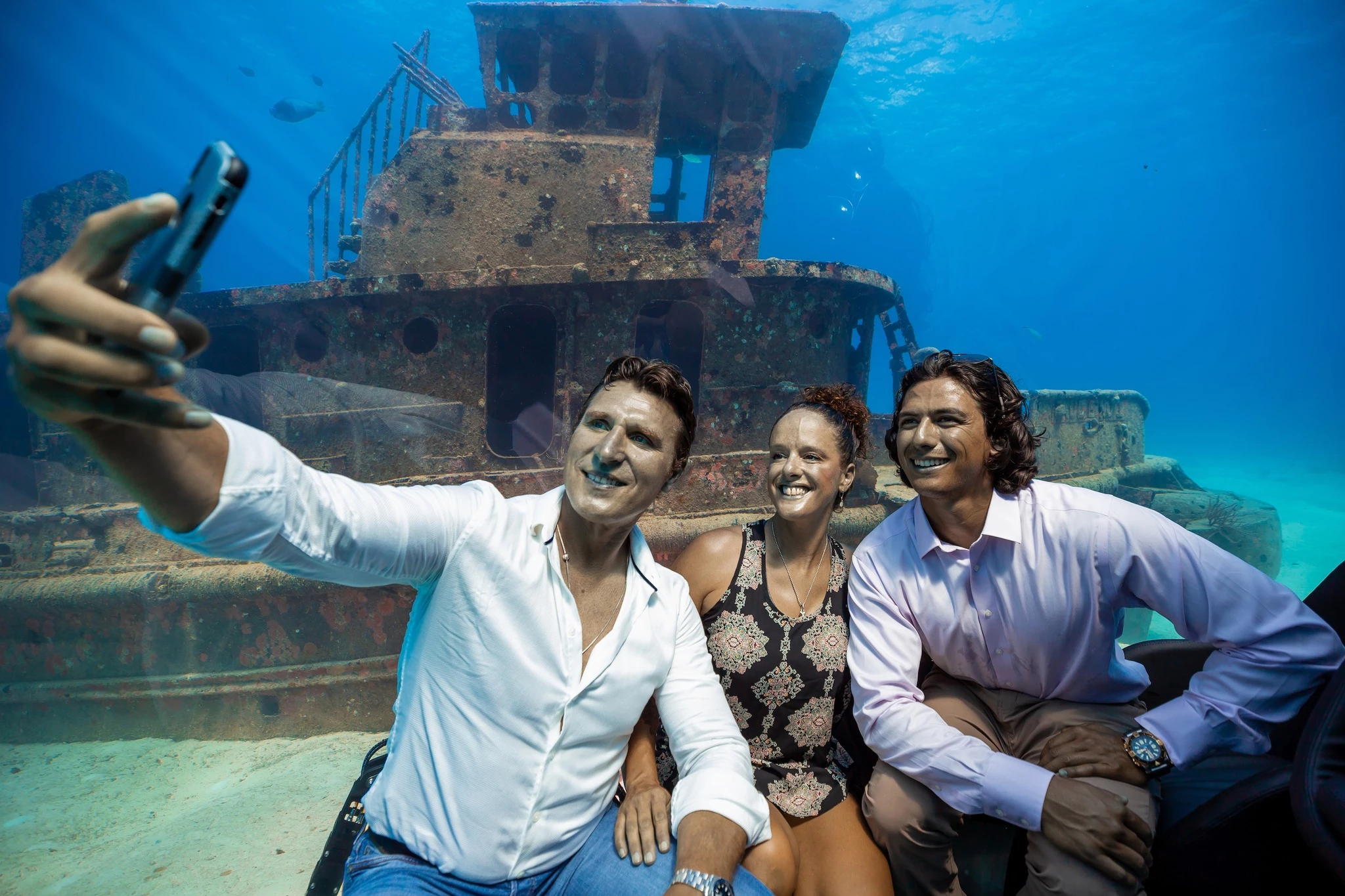

Since 2007, Triton has built some of the most innovative, high-tech and groundbreaking personal submarines on the market. Starting out with super-high-visibility acrylic bubble subs that deliver incredibly immersive underwater experiences in spacious, air-conditioned comfort, the company went on to create a "deep-sea elevator" that discovered new depths in the storied Mariana Trench, and now makes regular journeys to the very deepest parts of the ocean.

Triton hasn't manufactured that many submarines in its 16-year history – it's closing in on completing its 25th build. But every one of the remarkable vehicles it's made is still in service, and with the world reeling from the tragedy of the OceanGate disaster back in June – an entirely preventable loss of life that threatens to set the submarine industry back by decades – it's worth noting that certainly not everyone in this field is a total cowboy with a cavalier attitude to safety.

Skip to the end of this piece for Lahey's comments on OceanGate – the rest of this interview was recorded before the incident, so it won't otherwise be mentioned.

In part one of our candid chat, Lahey talks us through the start of his career as a commercial diver, and how some early experiences in Mantis subs designed by Graham Hawkes derailed his plans, setting him on a path that would take him to the bottom of the ocean.

What follows is an edited transcript, in his own words.

Early days as a commercial diver

I grew up about as far away from the ocean as you could be, in a place called Ottawa, Canada. I didn't see the ocean until I was about seven, when my parents moved to Barbados, because my dad was building some houses down there.

When I got to see the ocean for the first time, I was completely smitten. I really fell in love with the ocean. I lived in Barbados from the time I was seven till the time I was 10. Then I moved back to Canada. And when I got old enough to learn how to dive – 13 – I begged my father to let me become a scuba diver.

So I took a scuba diving course when I was 13, in about 1975. And much to my parents horror, when I turned 18, I told them that I didn't want to go to university, I wanted to go to a commercial diving school. They might have been happier if I had told them I was going to become a f*ckin' bank robber. Because then I might've had a fighting chance of financial success!

They might have been happier if I had told them I was going to become a f*ckin' bank robber.

But that's what I chose. And at 18, I went to this diving school, and I started in my commercial diving career. And I did well. It was the first time I actually did well at anything! But I did. I was the best in my class, because I think I was finally doing something that I was really interested in. I mean, everything that I was given I would devour.

I was interested in both the practical aspects of diving, but also all of the physiology and the other things that you needed to learn, if you really wanted to understand what was what was happening to you as a diver. I was very lucky, I went to work for a diving Company in Santa Barbara, California.

The diving thing was what I was really fixated on, I really wanted to do deep saturation diving, I was gonna be a big sat diver and all that. But the subs kind of intruded on that.

Enter the submarine

I think I was 21 when I first got to dive in a sub. And the sub experience ... as a diver, you know, you have to go through all kinds of really punitive, time consuming decompression. The sub changed my life because you could go from 1,400 feet (427 m) back up to the surface, and just have lunch. And you could go like four times deeper than I could as a diver. And I just thought, what a magical idea that you don't have those traditional limitations that I had become accustomed to as a diver.

Working as a diver at any sort of depth is incredibly difficult, because most of your effort is just expended in breathing. The gas that you breathe, which is a combination of helium and oxygen, is so thick that it's like soup, so I don't know how productive you can be. But in the sub, I went down much deeper, spent an hour or two driving around a blowup preventer, and then came right back up. Boom. Pretty awesome stuff.

That sub belonged to International Underwater Contractors, a diving company based out of New York, in the Bronx. And it was formed by a really interesting man named Andre Galerne. Andre was one of those incredibly brilliant and accomplished divers that came out of the south of France, like Cousteau and Gagnan and Delauze, who founded Comex. So my boss there was a real pioneer, like so many of those guys were. And I was lucky enough to go to work for him.

The experience of making that first dive made such an indelible impact that I just decided at that moment that I was going to pivot.

When I worked for IUC as a diver, they had a bunch of subs. In those days, they were still using subs in the oil and gas industry. So it just kind of happened by coincidence – I was out there working for them as a diver. And I was pretty good at fixing stuff and all that. And so one day, they said, hey, would you like to learn about the subs? And I said, yeah I'd be very interested. They had a thing called a Mantis in there, which was like a sub, they called it an ADS suit – atmospheric diving suit.

Essentially, these were like submarines that you wear. Single person, on a tether that could be deployed, and they'd allow you to go to much greater depths than you could as diver, but you stayed at one atmosphere, and as a consequence, didn't have all the decompression and all those other things. ADS suits were quite popular in the late 70s, early 80s.

So the Mantis, you might know it from The Spy Who Loved Me. The guy that invented the Mantis was called Graham Hawkes, brilliant submarine designer. He had a company called Offshore Submersible Engineering Limited.

They developed the Mantis, and they also developed the Wasp, which was like a vertical version of the Mantis. In the Mantis you lay down like on a couch. And in the Wasp, you were standing upright, and you had pedal controls on the floor. And interestingly, in the James Bond film, if you look carefully in the sub that's, you know, trying to drill a hole in the other sub, that's Graham driving!

And eventually, I got to drive one too. I operated a bunch of Mantis, I don't know, more than a dozen of them. I think they made around 30 of them. I think the experience of making that first dive made such an indelible impact that I just decided at that moment that I was going to pivot, I was going to try and work with these subs because I thought they were fantastic.

There's something magical about the idea of getting in a machine, going down into extreme depths, and then coming right back up and getting out. I just thought it was a super cool idea. And here we are 40 years later, and I'm still playing around with subs.

On the fatal OceanGate Titan submersible implosion in June 2023 (prepared statement)

The commercial tourism and private submersible sector has a 40-year unblemished safety record operating fully certified submersibles. Each has followed an arduous set of regulations that govern design, construction, testing, pilot training and operational aspects, allowing literally millions of passengers a year to dive in complete safety over the last four decades.

While everyone in the sector will no doubt look to see if any lessons can be learned from this tragic event, it should be very clear to everyone by now that the events in the North Atlantic, the manner in which the operation was run and the experimental nature of the craft, bears no relation whatsoever to a highly professional, safe and accomplished sector.

The fact is the existing system isn’t broken, an outlier that didn’t respect or follow any universally accepted, established and proven guidelines generated the inevitable result it did.

Stay tuned for part 2 and part 3 of this interview in the coming days, in which we follow Lahey through the difficult early years of Triton Submarines, and the key innovations and extraordinary achievements that followed.

Source: Triton Submarines