Immunotherapy is a promising new form of cancer treatment, but the supercharged immune cells it employs can become exhausted in the fight. Researchers in Japan have found a way to keep them going for longer, by rejuvenating them with stem cells.

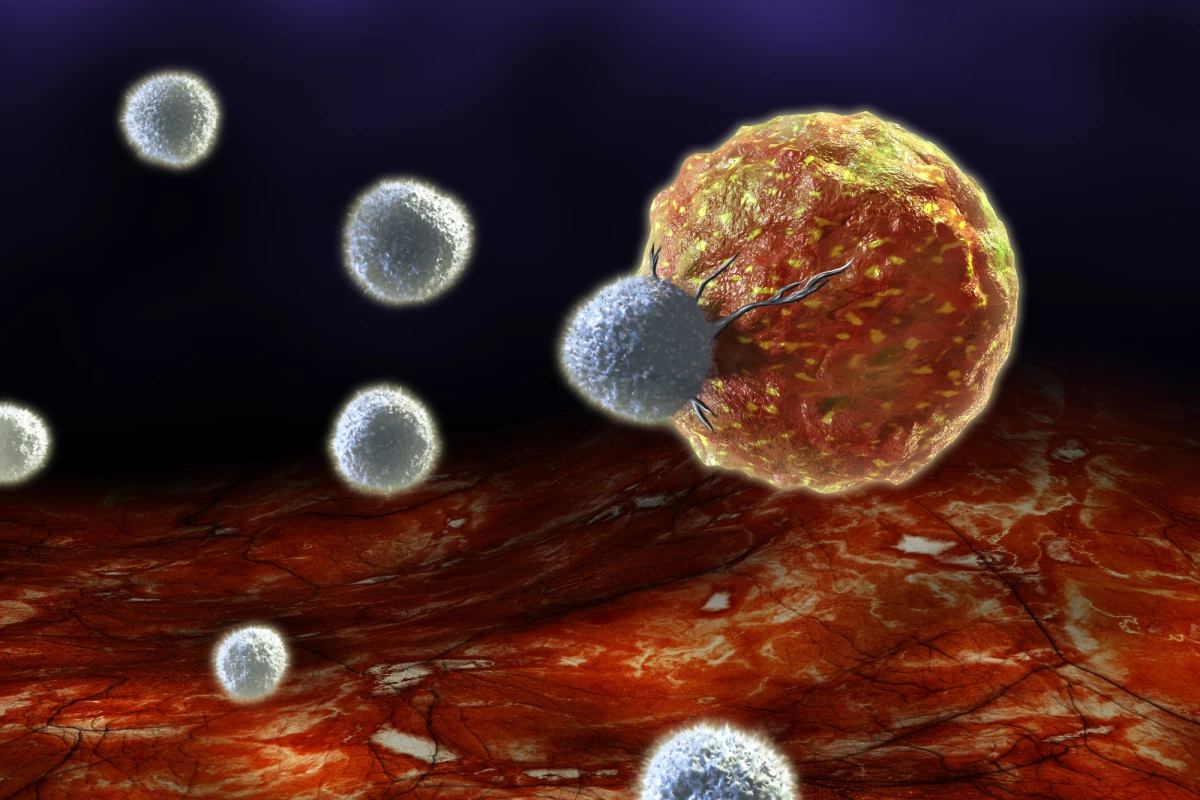

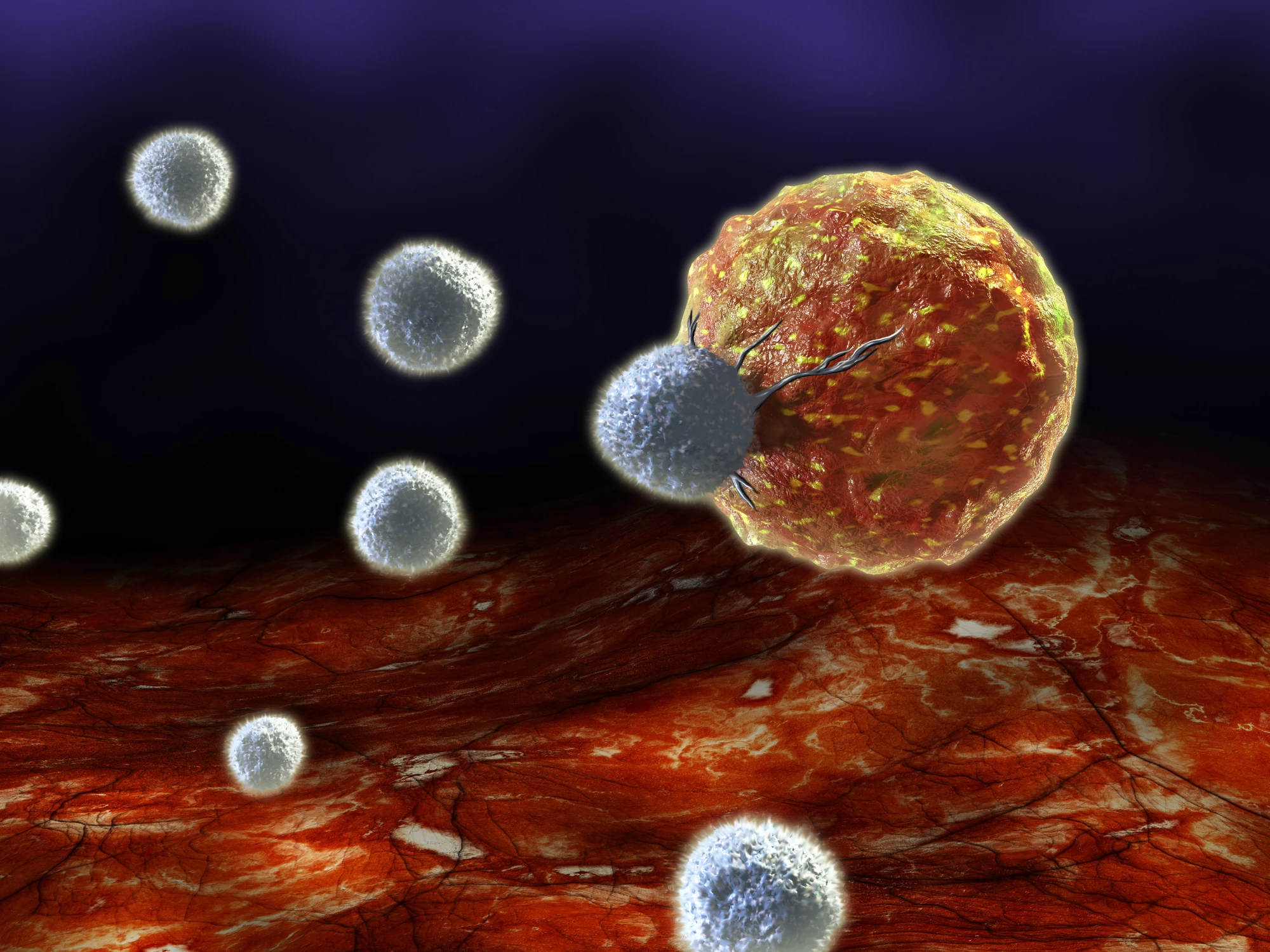

Our immune systems are our most powerful tools against cancer, but sometimes they need some help. Cancer has an arsenal of crafty tricks at its disposal to avoid detection, or weaken immune cells that try to attack it. CAR T cell immunotherapy is our way to try to turn the tide back in our favor.

Doing so involves removing immune cells from a patient, engineering them to recognize specific proteins found on cancer cells, and returning them to the body to get to work hunting that cancer down. While some trials have shown incredibly effective results, the T cells can become exhausted with time and lose their effectiveness, giving the cancer a chance to bounce back.

Finding ways to reduce that exhaustion could be a crucial part of improving immunotherapy. Past work has identified signaling proteins and genes that seem to make immune cells vulnerable to exhaustion, and inhibiting or deleting these is being explored as a way to keep the cells from burning out.

In the new study, researchers from Juntendo University in Japan developed a different method. They started with T cells that specifically seek out a cancer protein called LMP2, and wound back the clock to turn them into what are called induced pluriopotent stem cells (iPS cells). Then, the team added a receptor that recognizes a different cancer protein called LMP1. The end result is “rejuvenated” T cells that not only resist exhaustion for longer, but can target both cancer proteins.

“These rejuvenated T-cells essentially have dual receptors; so, they recognize and are active against both LMP1 and LMP2,” said Dr. Miki Ando, corresponding author of the study. “That is why we named them dual receptor rejuvenated T-cells, or DRrejTs.”

The researchers tested the treatment in mice with lymphoma, and found that the treated animals survived much longer, with all of them living more than 100 days. Better yet, when more cancer cells were injected into the mice later on, the treated mice suppressed tumor formation again. This indicates that the DRrejT cells remained active for long periods of time. Further tests targeted a different protein, CD19, instead of LMP2, and found similarly effective results.

Although further work is needed, the team says that the research could lead to more effective immunotherapies for human patients.

“If we are able to engineer DRrejTs that can avoid host rejection by immune cells of patients with cancer, we might have the answer to a ready, ‘off-the-shelf’ therapy for different cancers,” said Dr. Sakiko Harada, the first author of the study.

The research was published in the journal Molecular Therapy.

Source: Juntendo University