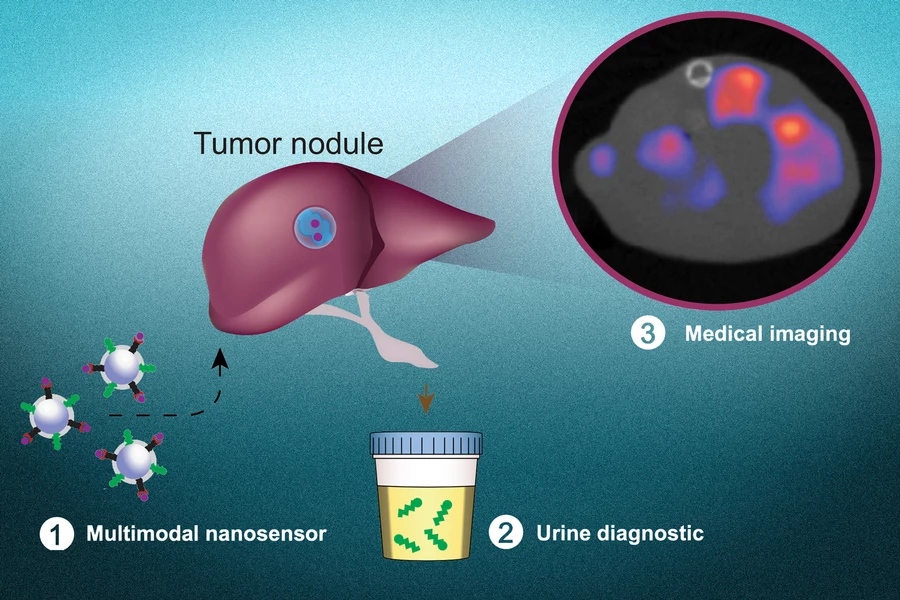

The earlier cancer is detected, the better the outcome for the patient. Now, researchers at MIT have developed a new diagnostic system that can be performed as a simple urine test to detect the presence of cancer, and if a positive is returned, a follow-up test can locate where it is in the body.

The MIT system is built around a specially designed nanoparticle that can produce “synthetic biomarkers” in urine if a person has cancer, and in previous tests it has proved promising at this job. But the problem is, it couldn’t tell where in the body the tumors were located. Now, the team has added this function.

The method by which the nanoparticles detect cancer is quite clever. To escape their point of origin and spread throughout the body, many cancers use enzymes called proteases which slice through proteins in the extracellular matrix. The diagnostic nanoparticles are coated in peptides that can also be cut up by these proteases, so if there are tumors present somewhere, the nanoparticles will bear the scars of their encounters by the time they reach the urine.

Knowing if you have cancer and knowing where it is are two very different questions, so to help answer the second one, the team tweaked the nanoparticle recipe. They added a peptide that is attracted to acidic environments like those that tumors produce around themselves, meaning the nanoparticles tend to cluster around cancer. They also added copper-64, a radioactive tracer that glows under PET imaging.

This means the nanoparticles will gather at the site of tumors and be clearly visible under a PET scan. The team says that this method makes tumors stand out better than commonly used PET tracers, which can also make organs like the heart glow strongly and potentially wash out any nearby cancer signals.

The team tested the particles on mice with metastatic colon cancer, and were able to track how they responded to chemotherapy. In the long run, if it makes it to human use, the researchers envision the test becoming part of an annual health check.

“Every year you could get a urine test as part of a general check-up,” says Sangeeta Bhatia, lead author of the study. “You would do an imaging study only if the urine test turns positive to then find out where the signal is coming from. We have a lot more work to do on the science to get there, but that's where we would like to go in the long run.”

The research was published in the journal Nature Materials.

Source: MIT