The idea of using ultrasound to non-invasively target cancer is an appealing one that is gaining real traction, on the back of studies demonstrating how it can more effectively deliver drugs, selectively take out cancer cells and heat and destroy diseased tissue. University of Michigan (UM) researchers have been exploring how it can combine with the body's immune defenses to take out tumors through a one-two punch, with a new study on rodents returning some highly promising results.

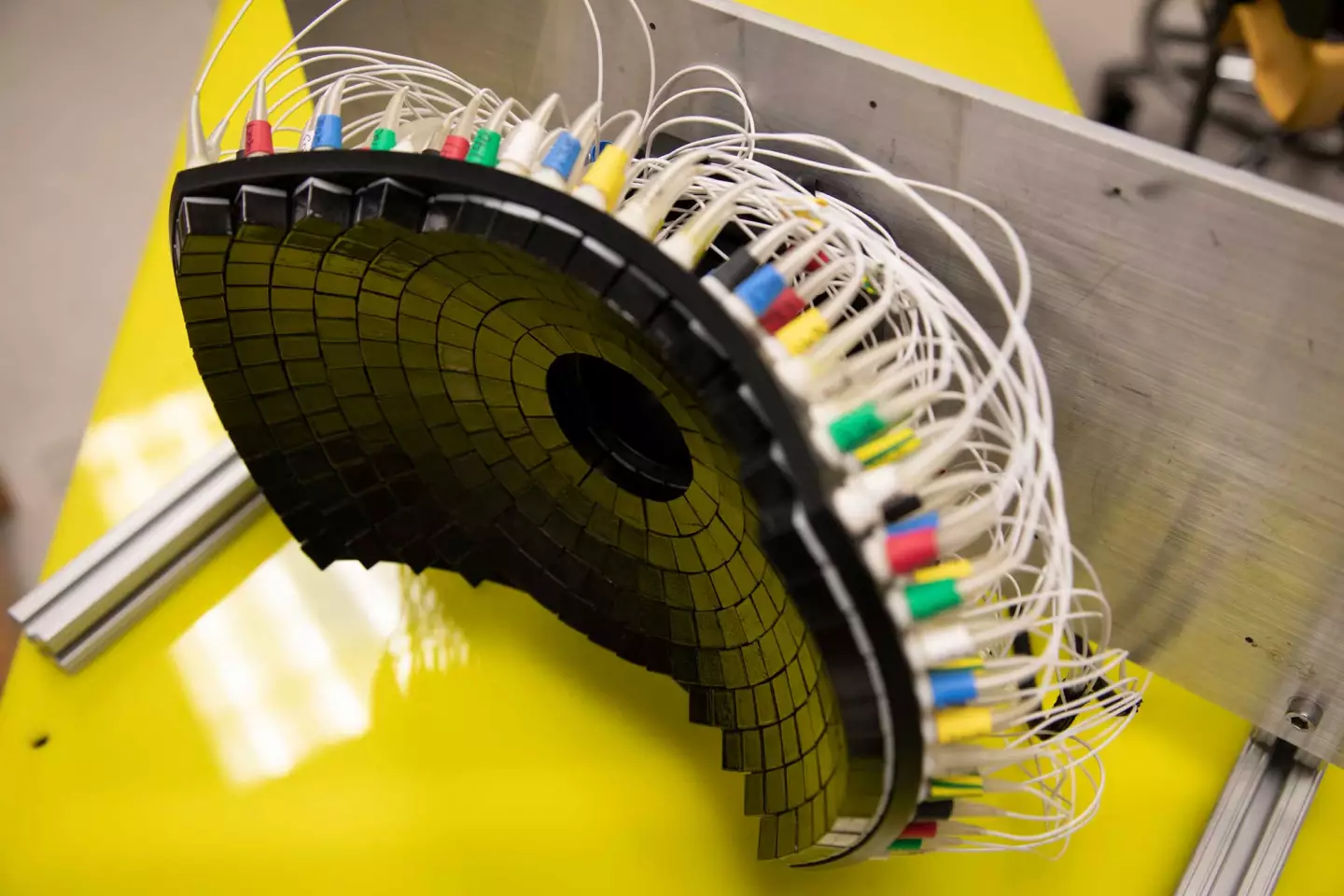

The technique under development by the UM team involved using ultrasound waves delivered in microsecond-long pulses to targeted tissues. Called histotripsy, the treatment leads to the formation of tiny bubbles in the tissue, which quickly expand and collapse in a violent manner, with the resulting mechanical stress killing cancer cells and dismantling the tumor's structure. The body is able to then harmlessly absorb the leftover debris.

This mirrors another technique we looked at from scientists in Israel in 2020, though in that method microbubbles are injected into the tumor rather than generated from the outside. Another point of difference with the UM team's approach is that it seeks to leverage the immune response induced through histotripsy. The scientists believe the debris left over from the tumor destruction contains the ingredients to stimulate what's known as immunogenic cell death, in which the immune system targets tumor cells.

In doing so, the scientists believe it may be possible to target only part of a tumor with ultrasound, and at the same time stimulate the immune system to take out the rest. This could prove useful in scenarios where a tumor cannot be targeted in its entirety, perhaps due to its size or location. To explore this idea, the scientists carried out experiments on rats where only 50 to 75 percent of liver tumors were destroyed with the ultrasound technique.

This is described as the first study to assess how partial histotripsy ablation impacts the ability of immune cells to infiltrate a tumor, and how that affects survival outcomes. Partially destroying the tumors while leaving portions intact indeed stimulated the rats' immune response, which cleared away the rest. There was no evidence of recurrence or metastasis in 80 percent of the rats treated this way.

“Even if we don’t target the entire tumor, we can still cause the tumor to regress and also reduce the risk of future metastasis,” said Zhen Xu, corresponding author of the study.

The researchers say the exact mechanisms behind the destruction of the left over tumor is unknown and while likely a result of immunogenic cell death, further studies are needed to confirm it. The next steps will also explore how the technique could be adapted to treat tumors at different stages of progression, with those used in this study at an early stage only.

“Histotripsy is a promising option that can overcome the limitations of currently available ablation modalities and provide safe and effective noninvasive liver tumor ablation,” said study author Tejaswi Worlikar. “We hope that our learnings from this study will motivate future preclinical and clinical histotripsy investigations toward the ultimate goal of clinical adoption of histotripsy treatment for liver cancer patients.”

The research was published in the journal Cancers.

Source: University of Michigan