ZeroAvia is working with San Francisco startup Verne to bring an even more energy-dense form of hydrogen to the clean aviation space. Cryo-compressed H2 could reduce costs, speed up fueling, and unlock 40% more flight range than cryogenic liquid H2.

Hydrogen is a pain in the butt. It's hard to store and transport, requiring either ultra-cold temperatures, or energy-hungry compression to get it into a useful volume. It's energy-inefficient to make, and there's no distribution network for it per se.

But if you want to decarbonize aviation, it's one of your only real fuel options. It might not carry as much energy as jet fuel, but it gives you a huge energy density boost as compared with lithium batteries. Hence, companies like ZeroAvia are working around the clock to get it tested and validated for use in commercial aircraft. Gaseous hydrogen fuel cell test flights are already well and truly underway – even at small airliner scale – and last year saw the first ever manned flight of an aircraft running on liquid hydrogen – a next-gen solution that should boost range significantly.

Now, ZeroAvia is looking to bring a third form of hydrogen fuel into the conversation, capable of carrying even more energy.

The idea of cryo-compressed hydrogen (CcH2) has been around for more than 25 years. It was first proposed as a high-density energy medium by Salvador Aceves at Lawrence Livermore National Labs, BMW created prototypes of a CcH2 system for passenger cars more than 10 years ago, and Cryomotive is one of a number of companies now looking to bring its benefits to long-haul trucking, promising the range and quick fueling time of diesel in a zero-emissions fuel that stores more than 3,000 Wh/kg.

So what is it? CcH2 effectively combines the cryogenic cooling used to liquefy hydrogen with some of the compression used to store gaseous hydrogen. Where liquid hydrogen requires temperatures under 20 K (−253 °C/−423 °F) at ambient pressure, and gaseous hydrogen tends to be compressed into the 700 bar range at ambient temperatures, CcH2 shoots for a practical point in between, and can deliver significantly higher storage densities.

Say you keep the hydrogen at 20 K, then compress that to 240 bar. According to Langmi et al, the volumetric hydrogen storage increases from 70 g/liter to 87 g/liter. But you also greatly reduce, or potentially even nearly eliminate, the boil-off losses endemic to liquid H2 storage. And you can refill at the speed of liquid transfer, without needing millions of dollars' worth of compressor equipment at every fueling station.

As Composites World explains, you can also use much lighter tanks, or build them from cheaper materials, because you don't need to handle 700 bar pressure levels. And you don't need to supply active cooling in your vehicle; the insulated tank maintains its cryogenic temperature by itself, since every time you use fuel, the remaining fuel expands into the tank and thermodynamics lowers the temperature.

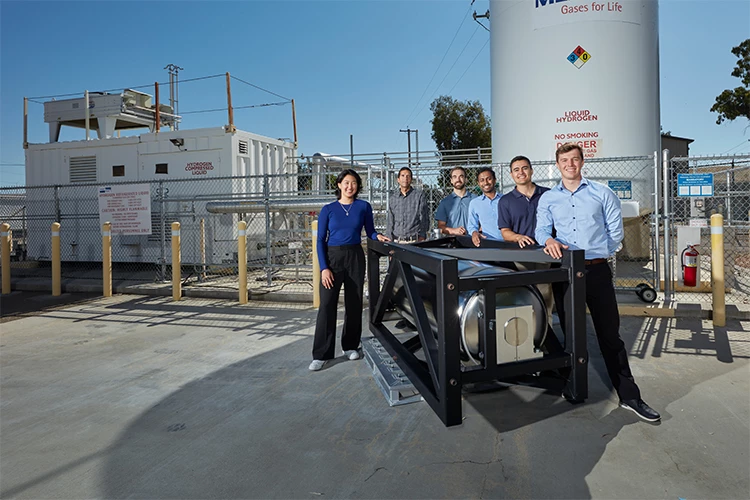

And thus to ZeroAvia's new MOU with Verne. Verne worked with Lawrence Livermore National Labs last year to demonstrate a CcH2 system running at undisclosed pressure and temperature levels, but capable of storing 27% more hydrogen than the same size liquid H2 system.

Verne believes it can get its CcH2 technology up to a "40 percent greater usable hydrogen density than liquid hydrogen," and it's now working with ZeroAvia to "jointly evaluate the opportunities" for CcH2 in aviation, as well as investigating the ground-based infrastructure required for fast refueling at airports.

It'll be interesting to see where this goes. In a Composites World interview, Cryomotive's Tobias Brunner explained that his company believes its CcH2 storage could be "a good fit for aviation" – but only in smaller planes, since once you move to very large tanks holding hundreds or thousands of kilograms of fuel, liquid hydrogen takes back over as the more lightweight solution at the system level. We wonder if Verne has a different approach to try.

Source: ZeroAvia