A revolutionary cryogenic tank design promises to radically boost the range of hydrogen-powered aircraft – to the point where clean, fuel-cell airliners could fly up to four times farther than comparable planes running on today's dirty jet fuel.

Weight is the enemy of all things aerospace – indeed, hydrogen's superior energy storage per weight is what makes it such an attractive alternative to lithium batteries in the aviation world. We've written before about HyPoint's turbo air-cooled fuel cell technology, but its key differentiator in the aviation market is its enormous power density compared with traditional fuel cells. For its high power output, it's extremely lightweight.

Now, it seems HyPoint has found a similarly-minded partner that's making similar claims on the fuel storage side. Tennessee company Gloyer-Taylor Laboratories (GTL) has been working for many years now on developing ultra-lightweight cryogenic tanks made from graphite fiber composites, among other materials.

GTL claims it's built and tested several cryogenic tanks demonstrating an enormous 75 percent mass reduction as compared with "state-of-the-art aerospace cryotanks (metal or composite)." The company says they've tested leak-tight, even through several cryo-thermal pressure cycles, and that these tanks are at a Technology Readiness Level (TRL) of 6+, where TRL 6 represents a technology that's been verified at a beta prototype level in an operational environment.

This kind of weight reduction makes an enormous difference when you're dealing with a fuel like liquid hydrogen, which weighs so little in its own right. To put this in context, ZeroAvia's Val Miftakhov told us in 2020 that for a typical compressed-gas hydrogen tank, the typical mass fraction (how much the fuel contributes to the weight of a full tank) was only 10-11 percent. Every kilogram of hydrogen, in other words, needs about 9 kg of tank hauling it about.

Liquid hydrogen, said Miftakhov at the time, could conceivably allow hydrogen planes to beat regular kerosene jets on range.

"Even at a 30-percent mass fraction, which is relatively achievable in liquid hydrogen storage, you'd have the utility of a hydrogen system higher than a jet fuel system on a per-kilogram basis," he said.

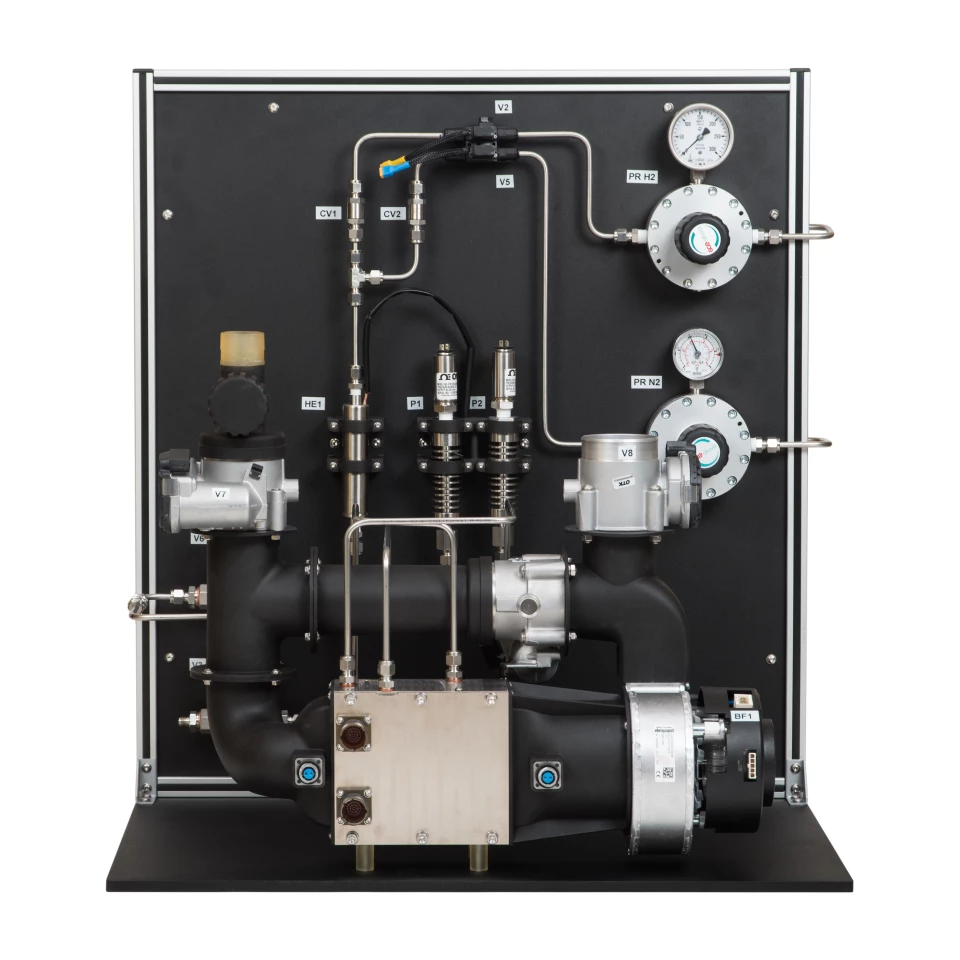

GTL claims the 2.4-m-long, 1.2-m-diameter (7.9-ft-long, 3.9-ft-diameter) cryotank pictured at the top of this article weighs just 12 kg (26.5 lb). With a skirt and "vacuum dewar shell" added, the total weight is 67 kg (148 lb). And it can hold over 150 kg (331 lb) of hydrogen. That's a mass fraction of nearly 70 percent, leaving plenty of spare weight for cryo-cooling gear, pumps and whatnot even while maintaining a total system mass fraction over 50 percent.

If it does what it says on the tin, this promises to be massively disruptive. At a mass fraction of over 50 percent, HyPoint says it will enable clean aircraft to fly four times as far as a comparable aircraft running on jet fuel, while cutting operating costs by an estimated 50 percent on a dollar-per-passenger-mile basis – and completely eliminating carbon emissions.

HyPoint gives the example of a typical De Havilland Canada Dash-8 Q300, which flies 50-56 passengers about 1,558 km (968 miles) on jet fuel. Retrofitted with a fuel cell powertrain and a GTL composite tank, the same plane could fly up to 4,488 km (2,789 miles).

"That's the difference between this plane going from New York to Chicago with high carbon emissions versus New York to San Francisco with zero carbon emissions," said HyPoint co-founder Sergei Shubenkov in a press release.

There's not a sector in the aviation world that shouldn't be pricking up its ears at this news. From electric VTOLs to full-size intercontinental airliners, there aren't a lot of operators that wouldn't want to dramatically boost flight range, reduce costs, eliminate carbon emissions or simply just reduce weight to increase cargo or passenger capacity.

It won't be simple – there's a ton of work to be done yet on green hydrogen production, transport and logistics, not to mention developing these tanks and aircraft fuel cells to the point where they're airworthy, certified and well-enough tested to be considered a no-brainer. But with these kinds of numbers on the table as carrots, and the aviation sector's enormous emissions profile acting as a stick, these tanks should surely get a chance to prove themselves.

Source: HyPoint/GTL