With the World Superbike Championship celebrating its 25th year in 2012, it is an ideal time to reflect on the profound influence the series has had on the development of the everyday motorcycle. The production-based World Superbike Championship Series is now unquestionably the most important global race series in terms of influencing buyer decision of sports motorcycles and performance accessories but as our research shows, it appears to be even more influential than that. Statistics sourced from lap-times and speed traps over the last decade indicate the rapid rate road-going sports motorcycles are improving racetrack laptimes. Indeed, today's showroom models on road tires, are now quicker than the fastest factory superbikes of just five years ago.

There are now four significant classes of international racing based on production machinery – Superbike, Superstock 1000, Supersport and Superstock 600. They all occur on the same day, on the same racetrack as part of the greater series that has grown around the World Superbike Championship, and by comparing the lap times and top speeds from the various categories, it's now possible to chart the extraordinarily rapid development of the roadgoing sports motorcycle.

In just a quarter century, the World Superbike Championships has gathered the impetus of being, as BMW so aptly described it in a press document earlier this year, as “the Premier League for production-based motorcycles.”

The Japanese motorcycle manufacturers have been playing their own horsepower version of the Space Race ever since Kawasaki's three-cylinder 74 bhp H2 Mach IV arrived in the early seventies - each time a new "fastest motorcycle" appeared, it was usually just a short time before another came along that was faster again ... and they were all Japanese, because no-one else had the technology at that time to compete.

Throughout the period of Japanese horsepower proliferation which began in the early seventies with the Honda CB750, Kawasaki H2, Z1 etc, the commonly agreed measure of a sports motorcycle was its standing quarter mile time.

When the World Superbike Championships were inaugurated, the competition between the Japanese manufacturers took on a whole new focus and instead of straight line speed, or the fastest acceleration times over a quarter mile time, World Superbike results quickly became a very significant factor in the purchasing decisions for the everyday sports motorcyclist.

Being able to directly identify with the machine on the circuit because it is based on the motorcycle you ride offers a whole new level of involvement in the sport which prototype racing (MotoGP) does not. In the same way that the masses more readily identify with touring car racing than Formula One, Superbike is a more accessible sport.

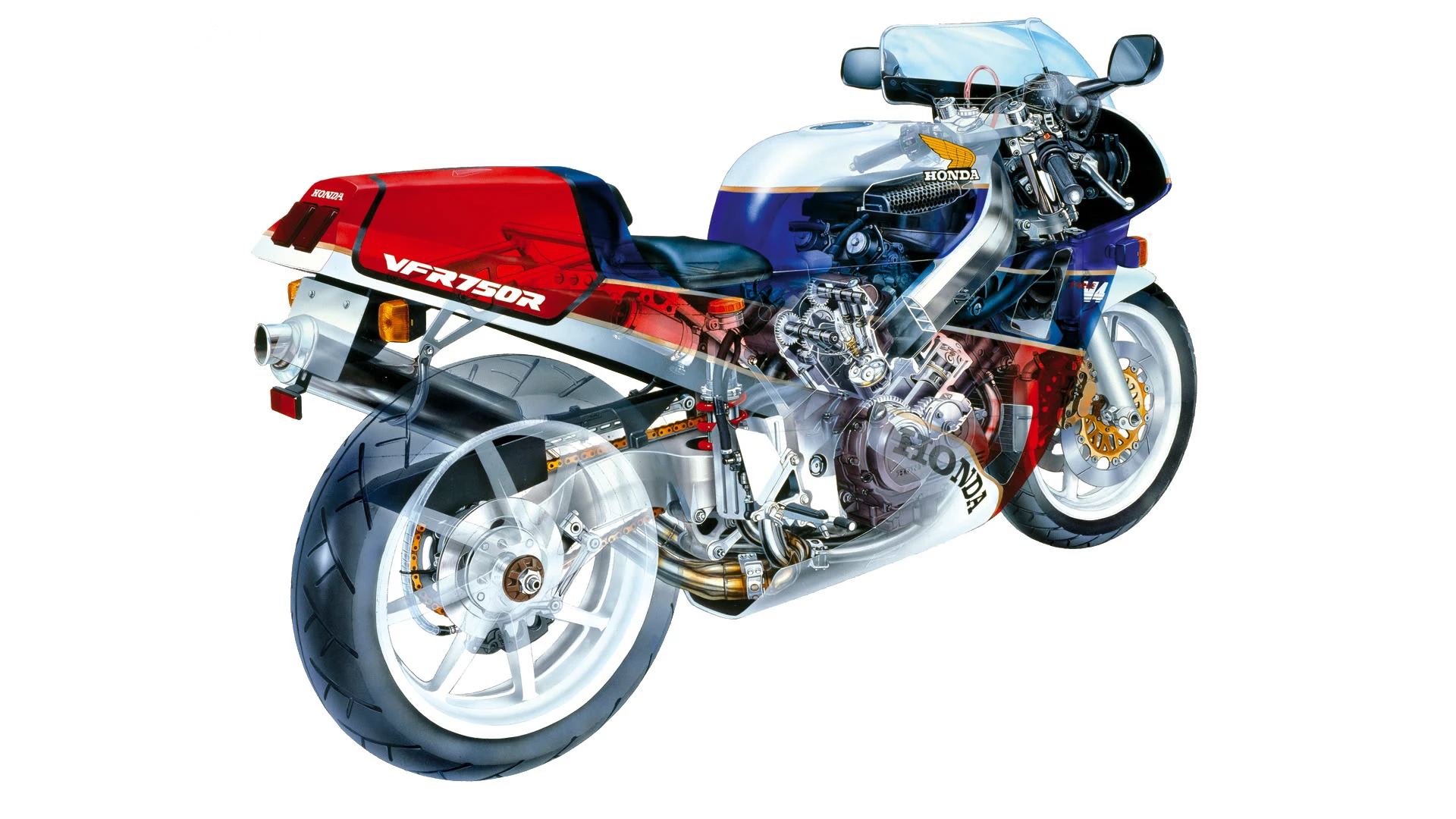

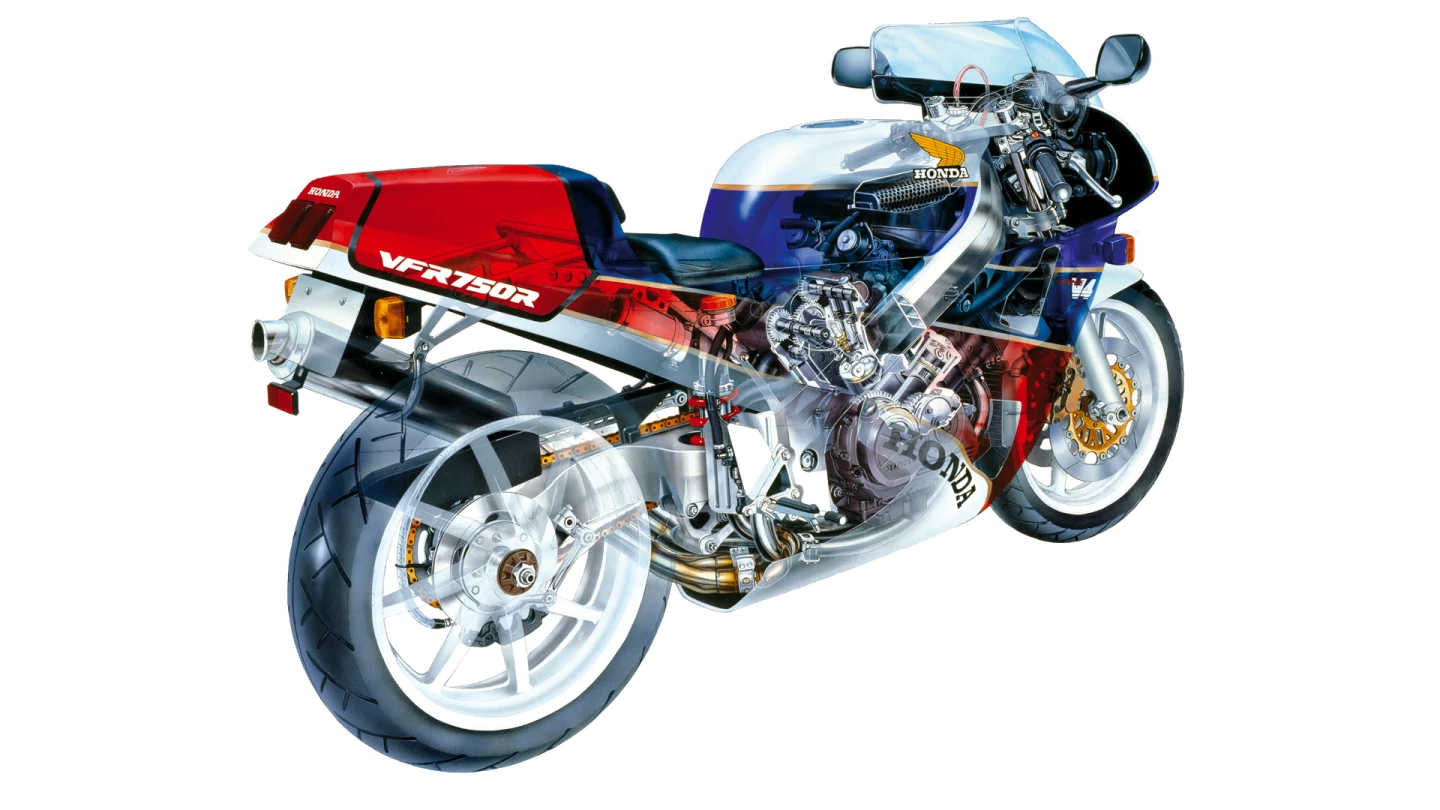

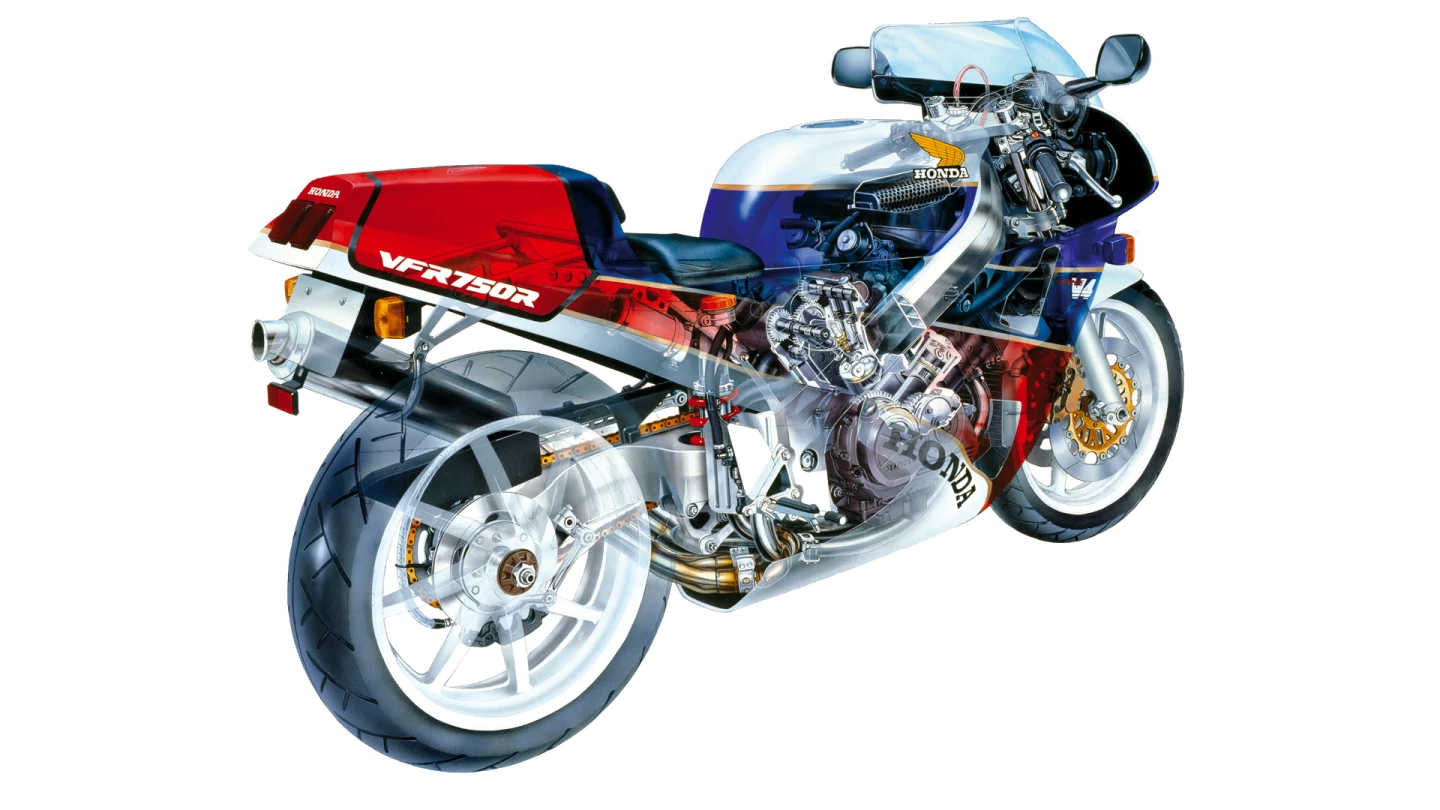

Recognising this potential, Honda built the VFR RC30 just to compete in the first championship in 1988. It was the first of many specially homologated motorcycles built with a view to taking the World Superbike Championship - the RC30's 748cc V4 produced just 86 horsepower in standard form, and no doubt a great deal more in superbike form. Indeed, towards the end of its production run, some showroom models were sold with 112 bhp.

A quick look inside leaves no doubt it was developed using many features of the Honda RVF endurance racer of the day, and the price tag reflected that as it was around double that of a normal 750 at the time.

For that money though, the RC30 had a full house of race oriented features such as a slipper clutch, 16 gear-driven valves, titanium connecting rods, one-sided quick change rear wheel, quick change brake pads, Showa race suspension ad infinitum.

Indeed, one of these bikes still holds the outright lap record for motorcycles for the legendary Nürburgring Nordschleife circuit, set in 1993 at 7:49.71 by Helmut Dähne.

By comparison, the motorcycle lap record prior to Dahne was set during the last (1980) 500cc German Grand Prix to be held at the circuit. On a Suzuki RG500 factory racer, Marco Lucchinelli clocked 8:22.2, some 30 seconds slower than Dahne.

American Fred Merkel won both the 1988 and 1989 titles on the RC30, before Ducati began its remarkable run of titles in 1990.

Though Ducati no longer wins most of the races as it once did, the Italian marque has won 281 World Superbike Championship races and 17 manufacturers titles in 24 years – all of the other manufacturers added together still can't match either of those numbers: Honda (101 wins and four titles), Yamaha (50 wins and one title), Kawasaki (37 wins), Suzuki (26 wins, one title), Aprilia (16 wins, one title) and Bimota (11 wins) are the only manufacturers to have won a race other than Ducati, though BMW appears set to add its name to the list before the year is out.

Just to be clear about the rules for those not familiar with them, the World Superbike Championship allow for production-based bikes with two, three or four cylinders. Three and four-cylinder bikes are restricted to 1,000cc, while bikes with two cylinder engines are limited to 1200cc. Three or four cylinder bikes must weigh at least 165kg, while bikes with two cylinders must weigh 171kg. All teams begin the season with a 50mm diameter air restrictor, and the weights of the bikes and size of the restrictor can be varied if one marque becomes either too dominant or uncompetitive.

Despite getting a leg-up with a larger capacity thanks to its V-twin engine, Ducati's results in World Superbike have been a major factor in establishing the premium Ducati brand of sports bike. It was the first non-Japanese marque for decades to challenge the dominance of the Japanese at their favourite game on the racetrack. All of the Japanese marques are fiercely proud of their racing heritage and have refined the art of building race bikes to the point where they are rarely beaten.

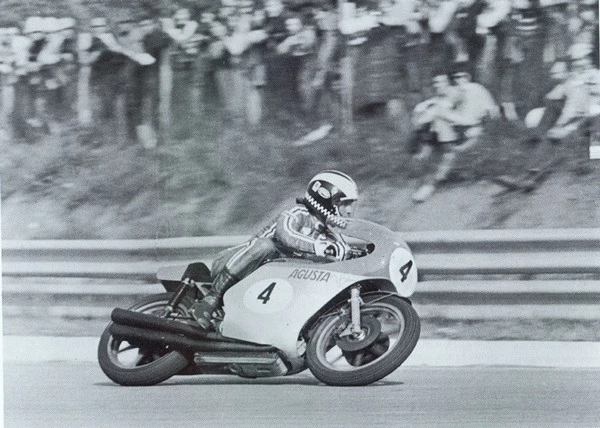

In the premier class of motorcycle racing, the World MotoGP (and previously 500cc Championships), the last non-Japanese bike to win a title was the MV Agusta of Phil Read in 1974 prior to Casey Stoner's win on the Ducati in 2007. That's a third of a century without a non-Japanese win, and it's hard to see a non-Japanese victory again in the near future.

So when the Japanese go racing, you can expect the pace to be hot.

As Superbike, Supersport and now the Superstock 1000 and Superstock racing categories have grown in stature and general recognition, the quest for better results has driven massive focus by the usual suspects (Honda, Yamaha, Suzuki, Kawasaki and Ducati), plus more recently BMW and Aprilia, into building ever more race-oriented roadgoing sports motorcycles upon which to base their factory superbikes.

Along the way, the organisers have attempted to frame a fair set of rules about what can and can't be modified. Hence more and more race special homologation models have been created.

When Aprilia went racing with the RSV4, it was aiming squarely at winning the Superbike title, so much so that it homologated a model where the motor could be repositioned in the frame, all of the steering geometry is variable, and the length and position of the swinging arm can also be changed. Just to ensure the gear ratios of the bike could be instantly tailored to any circuit, Aprilia added a cassette type gearbox to its V4 engine which can be swapped in a few minutes.

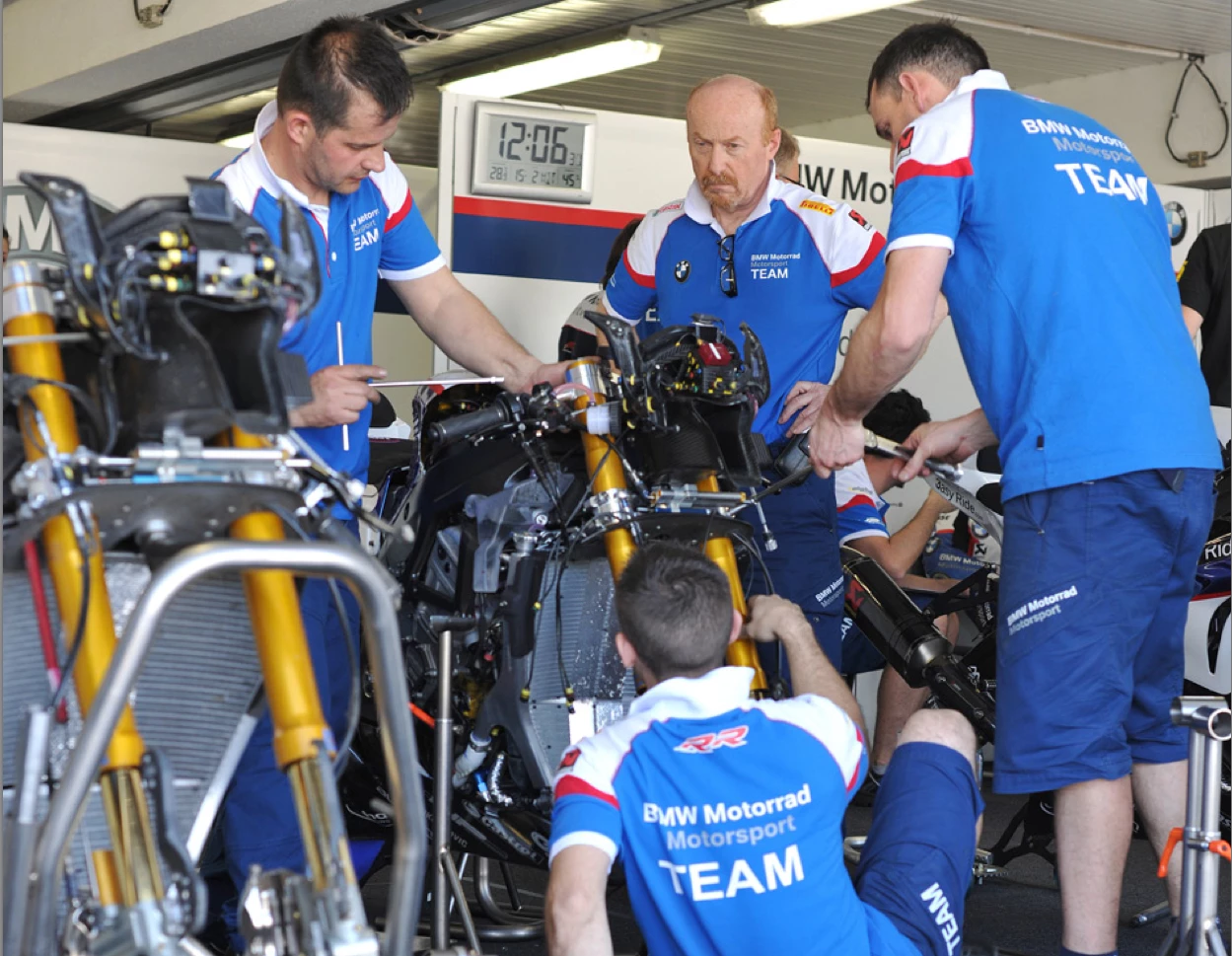

Superbike and superstock rules as they are framed, offer a reasonably fair comparison between a standard showroom motorcycle on control road tires and an identical base motorcycle that has been the focus of millions of dollars worth of development (i.e. a factory superbike) in every aspect of the engine and with the added advantage of the best suspension money can buy, plus of course, slick tires, plus a crew of experts in every aspect of a motorcycle's composite parts in attendance at all times.

Then there's the riders to consider – the top ten finishers in any superbike race are world class riders. Superstock riders are very good and getting better all the time as the series becomes recognised as a low-cost feeder league, but superstock riders are not at the same level as World Championship Superbike riders.

The superstock fields have traditionally been comprised of aspiring riders, but they are only part of the way along the journey – you'll see many recognisable names in these classes if you look back through the maze of statistics for each race which can be accessed in the World Superbike Championship site, but long before they were established as leading riders in the foremost categories. Riders in Superstock 1000 are restricted to being under 24 years of age, and riders in Superstock 600 are 20 or younger.

Hence although there is a direct comparison between Superbikes and Superstock 1000 and an identical comparison between Supersport and Superstock 600, there are many factors (tyres, level of support structure and rider quality just to begin with) which indicate that a stock motorcycle would be a lot closer to a superbike in both lap times and top speed if those other factors were also equal.

We had hoped that the fourth round of the 2012 title at Monza last weekend would present us with a perfect set of dry lap times to add to the previous years' lap times and top speeds we had assembled.

Sadly this was not to be, as the whole race three-day event was marred with sporadic rain which denied us a perfect comparison dry-track platform.

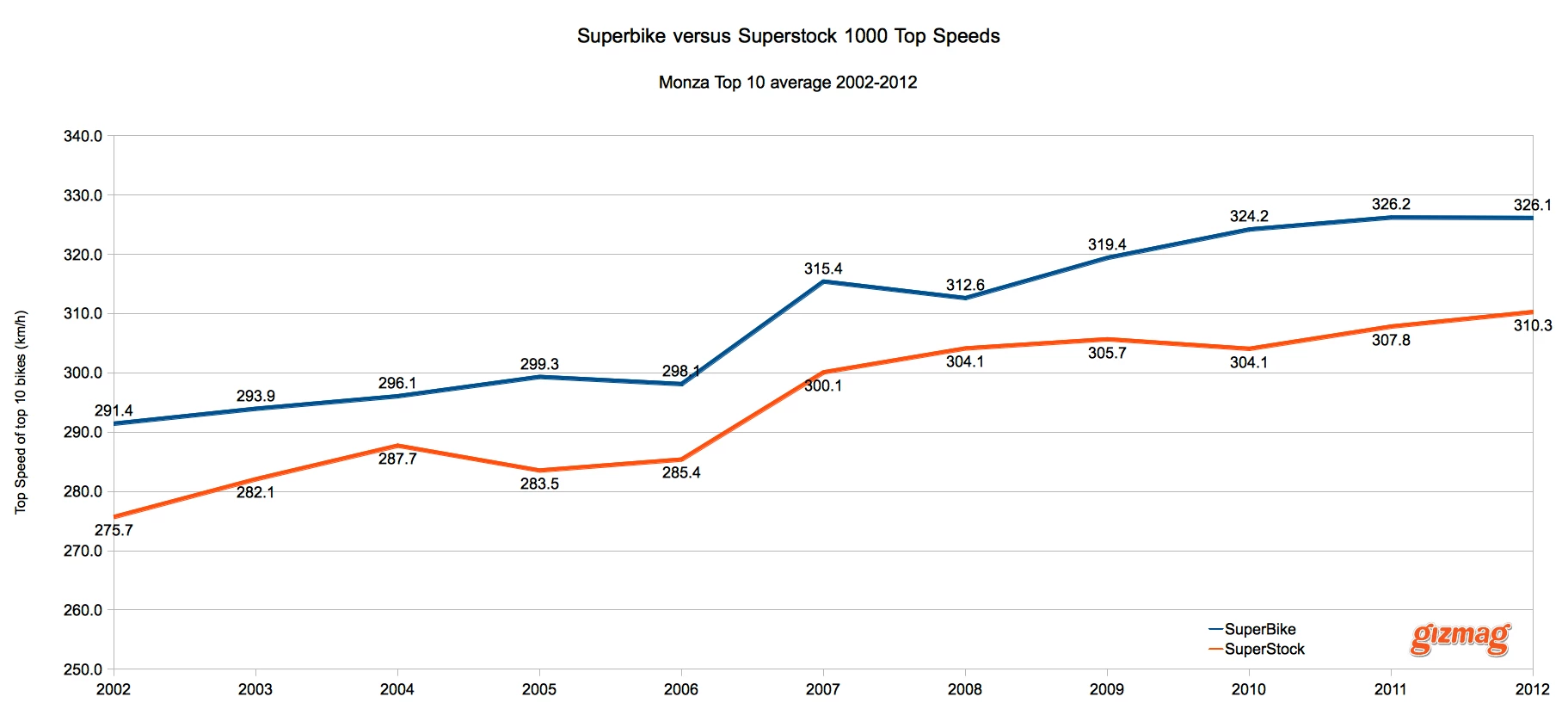

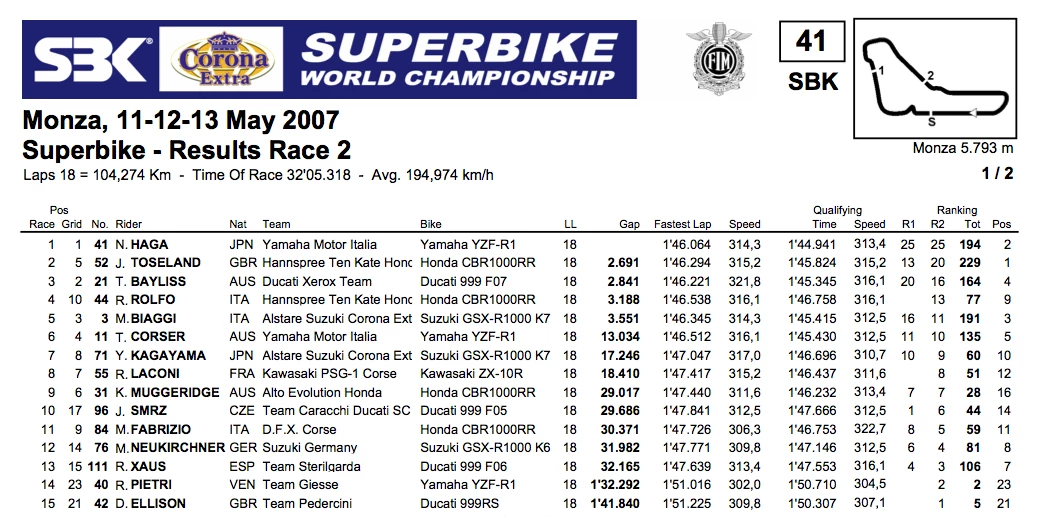

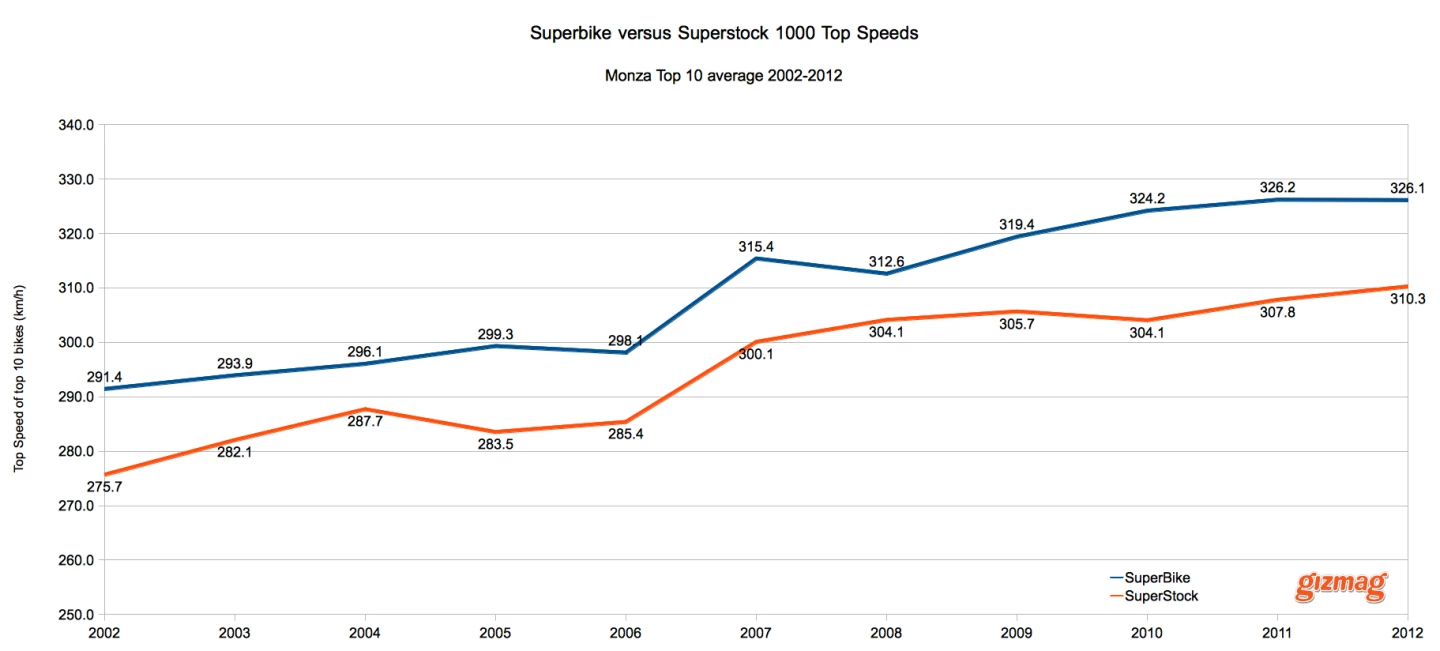

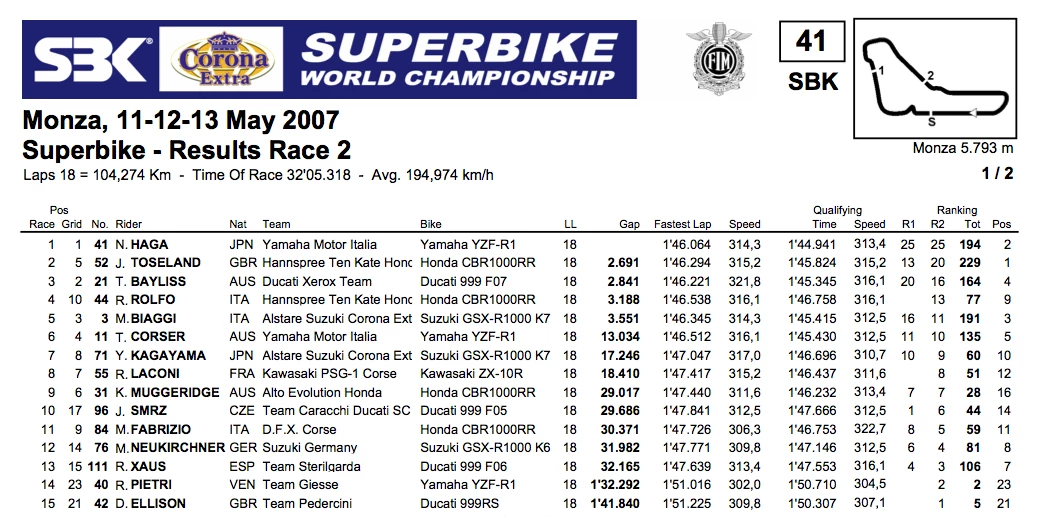

Before the event we prepared statistics showing the average best lap times of the top ten finishers in each of the Superbike and Superstock 1000 races held at Monza since 2002 (when Gizmag began), and similarly with the Supersport and Superstock 600 classes which have been running side-by-side since 2006.

We decided to use the top 10 average to ensure that the number we use is an indication of the speed of the overall field, and not just the result of one motorcycle with an excellent tuner.

As most of the sessions for the weekend were marred by rain of some sort, we used the best trap speeds and lap times from any session to arrive at our top ten average for the 2012 Monza round.

Here's what the average top ten lap times each year since 1999 looks like:

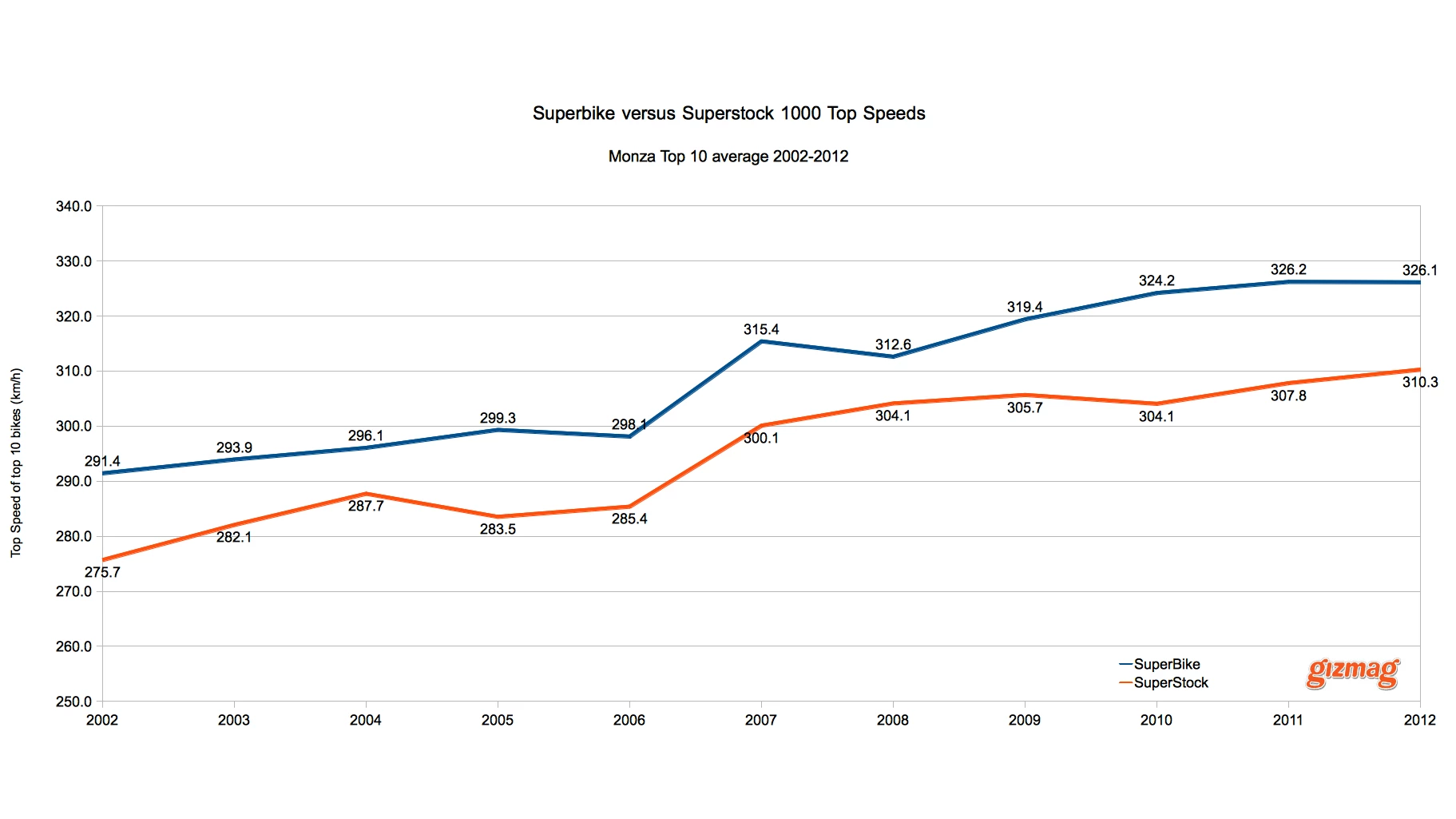

The thing I found most fascinating about this view of "motorcycle evolution" was that Superstock motorcycles, which are very representative of the bike on the showroom floor at your local dealership, are now lapping faster, on street tires, than the factory superbikes of just four to five years ago. I think it's safe to assume that any top ten finisher in a World Superbike Championship race has access to factory support and go-fast gear.

Obviously the lap times suffered due to the rain this year, because the average lap time of the top 10 improved 6.3 seconds in the previous eight years (2003-2011).

So the 106.6 second lap time average set by the Superstock 1000 bikes in 2011, on road tires

actually surpasses the top 10 average of the superbikes in 2007, on slick tires with full support crews and factory riders.

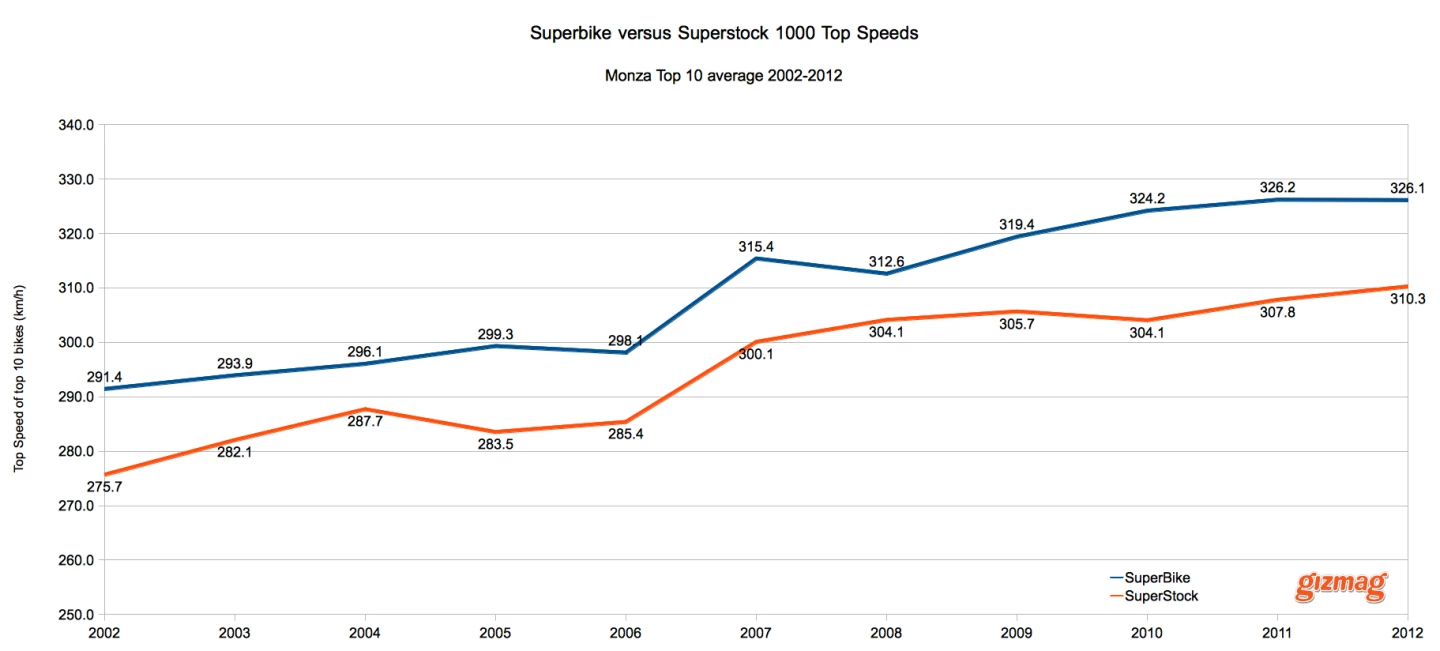

The top speed comparison is even more telling, with speeds improving by better than three km/h per year and the average top speed of the top ten Superstock bikes now faster than the Superbike top 10 of 2006.

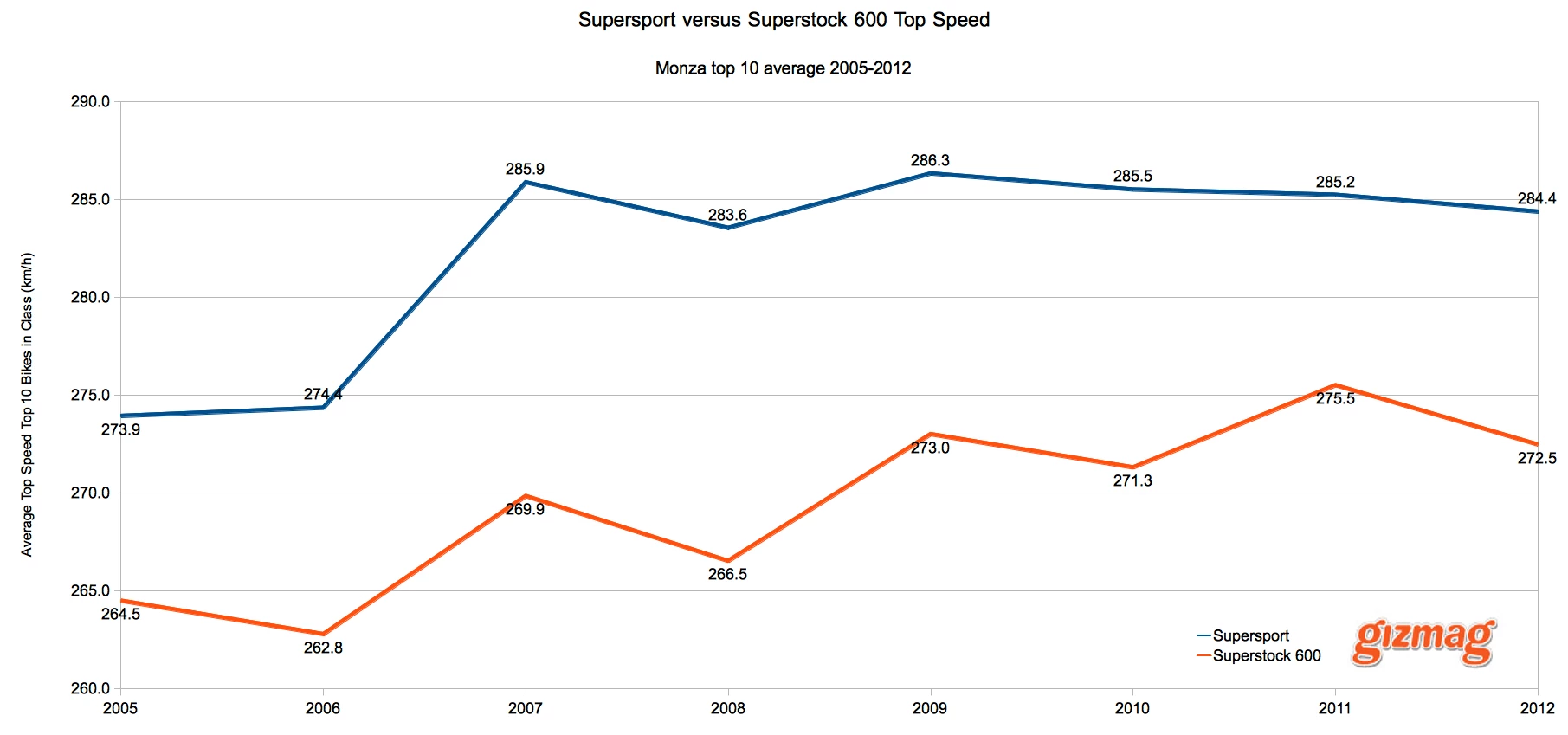

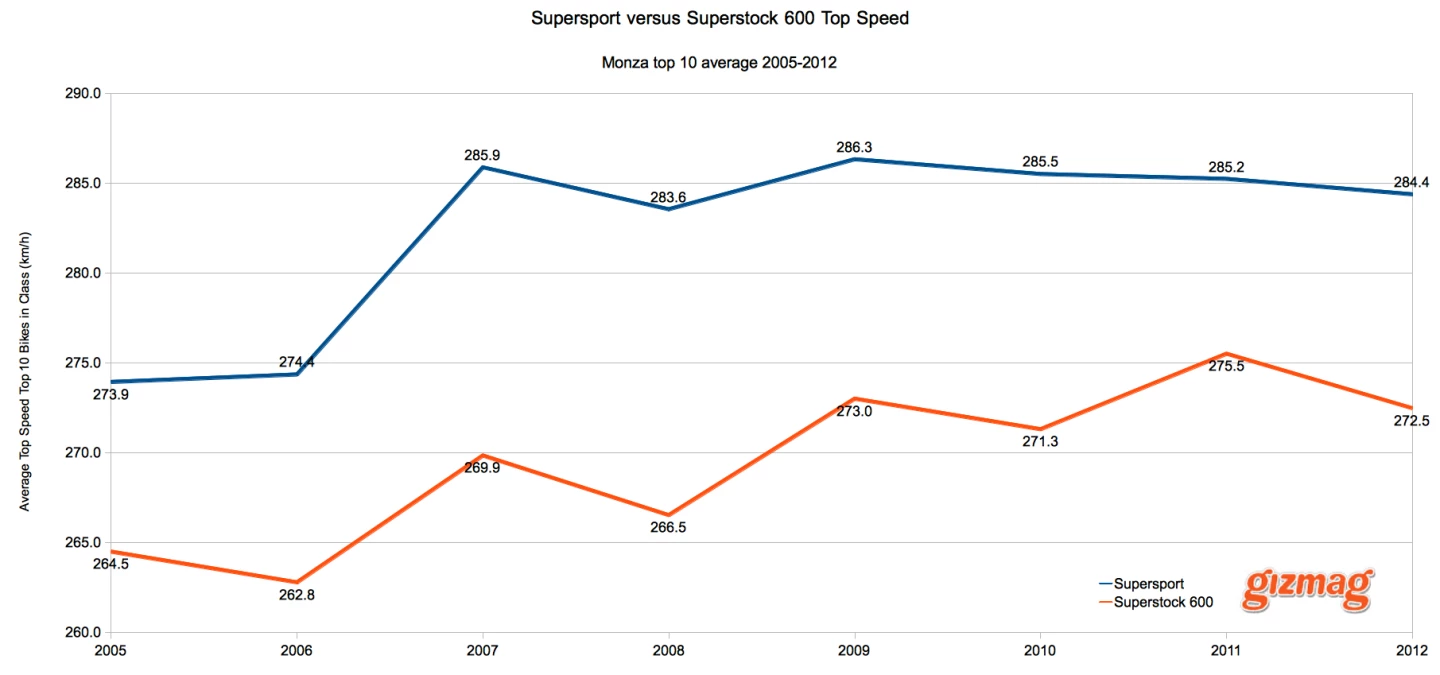

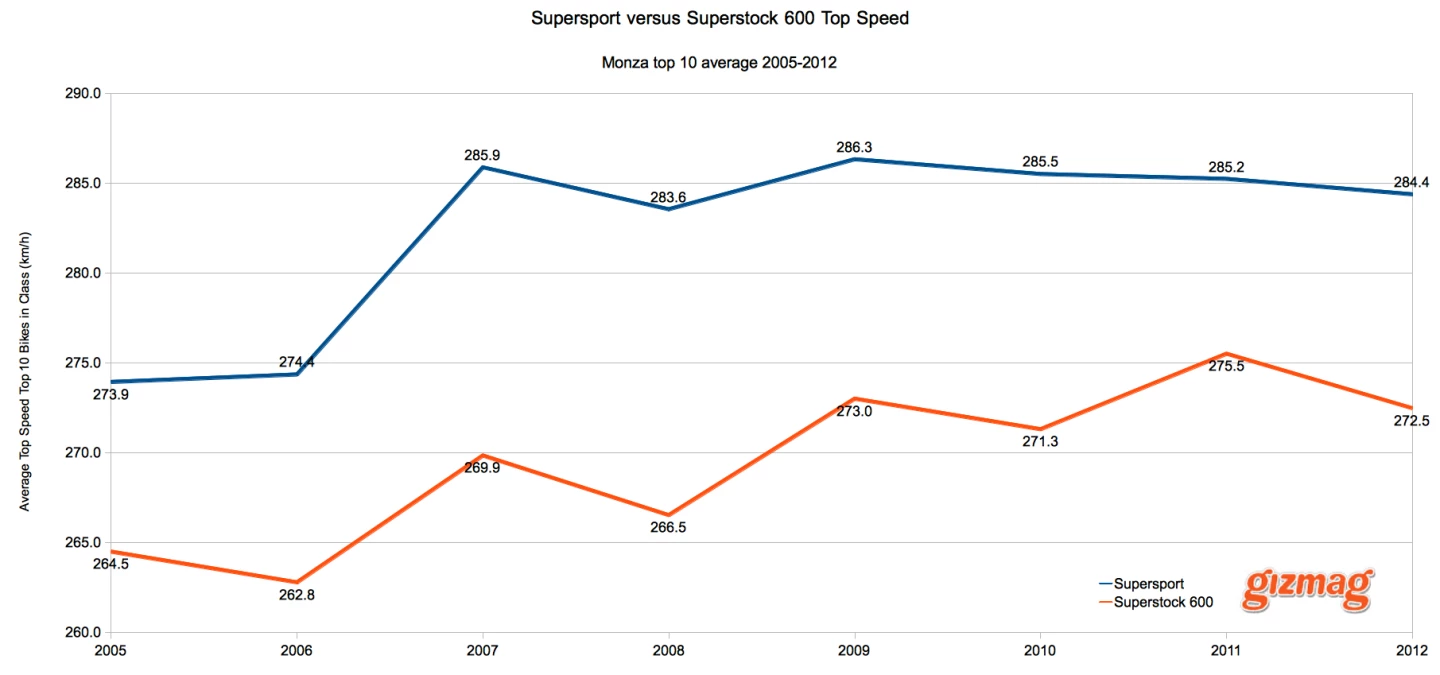

The equivalent average top ten lap times for the Supersport and Superstock 600 classes run as follows.

and average top ten top speeds showing similar improvement.

What we can see from these charts is that not only are stock motorcycles getting fast very quickly, the speed of the improvement of Superstock machinery appears to be as great, if not greater, than the speed of improvement of superbikes.

The speed of the showroom motorcycles we are now seeing is obviously tending towards the best that the factory can deliver, given the showroom models must pass ever more restrictive noise and emission standards. Indeed, it is hard to conclude anything other than that the range-topping showroom sports bikes are little more than mass-produced racebikes that can be registered for the road.

The engine, suspension and frame components are now being mass manufactured in high quality so efficiently that the amount of money you need to spend to get a small incremental perfromance advantage is now greater than ever – the factories have pushed the race-readiness of the 600cc and 1000cc class to the point where everything can be optimised cost-effectively already has been when it leaves the factory.

Hence to get something substantially lighter, you need exotic materials which cost a lot of money. If you want better suspension, there's a quantum leap in pricing to accompany the low production, high-craftsmanship replacements.

It all boils down to an extraordinary deal for the sports motorcyclist who is getting better and better machinery, with all the trickery that the factory superbikes use getting quickly incorporated into the next model of the road bike.

Now you might argue that it's a chicken-egg argument as to which comes first, but I'm certain that the reason for this extraordinarily rapid evolution of the ability of a road motorcycle to get from point A to point B is all down to the success and visibility of the World Superbike Championships.

I can't wait to see what happens a decade from now when both series of Superstock bikes will no doubt be running with World Championship status and the support structures behind the riders will be more substantial again.

I'm also really keen to see what our readership might be able to see in these figures that I haven't seen.

With the World Superbike Championship celebrating its 25th year in 2012, it is an ideal time to reflect on the profound influence the series has had on the development of the everyday motorcycle. The production-based World Superbike Championship Series is now unquestionably the most important global race series in terms of influencing buyer decision of sports motorcycles and performance accessories but as our research shows, it appears to be even more influential than that. Statistics sourced from lap-times and speed traps over the last decade indicate the rapid rate road-going sports motorcycles are improving racetrack laptimes. Indeed, today's showroom models on road tires, are now quicker than the fastest factory superbikes of just five years ago.

There are now four significant classes of international racing based on production machinery – Superbike, Superstock 1000, Supersport and Superstock 600. They all occur on the same day, on the same racetrack as part of the greater series that has grown around the World Superbike Championship, and by comparing the lap times and top speeds from the various categories, it's now possible to chart the extraordinarily rapid development of the roadgoing sports motorcycle.

In just a quarter century, the World Superbike Championships has gathered the impetus of being, as BMW so aptly described it in a press document earlier this year, as “the Premier League for production-based motorcycles.”

The Japanese motorcycle manufacturers have been playing their own horsepower version of the Space Race ever since Kawasaki's three-cylinder 74 bhp H2 Mach IV arrived in the early seventies - each time a new "fastest motorcycle" appeared, it was usually just a short time before another came along that was faster again ... and they were all Japanese, because no-one else had the technology at that time to compete.

Throughout the period of Japanese horsepower proliferation which began in the early seventies with the Honda CB750, Kawasaki H2, Z1 etc, the commonly agreed measure of a sports motorcycle was its standing quarter mile time.

When the World Superbike Championships were inaugurated, the competition between the Japanese manufacturers took on a whole new focus and instead of straight line speed, or the fastest acceleration times over a quarter mile time, World Superbike results quickly became a very significant factor in the purchasing decisions for the everyday sports motorcyclist.

Being able to directly identify with the machine on the circuit because it is based on the motorcycle you ride offers a whole new level of involvement in the sport which prototype racing (MotoGP) does not. In the same way that the masses more readily identify with touring car racing than Formula One, Superbike is a more accessible sport.

Recognising this potential, Honda built the VFR RC30 just to compete in the first championship in 1988. It was the first of many specially homologated motorcycles built with a view to taking the World Superbike Championship - the RC30's 748cc V4 produced just 86 horsepower in standard form, and no doubt a great deal more in superbike form. Indeed, towards the end of its production run, some showroom models were sold with 112 bhp.

A quick look inside leaves no doubt it was developed using many features of the Honda RVF endurance racer of the day, and the price tag reflected that as it was around double that of a normal 750 at the time.

For that money though, the RC30 had a full house of race oriented features such as a slipper clutch, 16 gear-driven valves, titanium connecting rods, one-sided quick change rear wheel, quick change brake pads, Showa race suspension ad infinitum.

Indeed, one of these bikes still holds the outright lap record for motorcycles for the legendary Nürburgring Nordschleife circuit, set in 1993 at 7:49.71 by Helmut Dähne.

By comparison, the motorcycle lap record prior to Dahne was set during the last (1980) 500cc German Grand Prix to be held at the circuit. On a Suzuki RG500 factory racer, Marco Lucchinelli clocked 8:22.2, some 30 seconds slower than Dahne.

American Fred Merkel won both the 1988 and 1989 titles on the RC30, before Ducati began its remarkable run of titles in 1990.

Though Ducati no longer wins most of the races as it once did, the Italian marque has won 281 World Superbike Championship races and 17 manufacturers titles in 24 years – all of the other manufacturers added together still can't match either of those numbers: Honda (101 wins and four titles), Yamaha (50 wins and one title), Kawasaki (37 wins), Suzuki (26 wins, one title), Aprilia (16 wins, one title) and Bimota (11 wins) are the only manufacturers to have won a race other than Ducati, though BMW appears set to add its name to the list before the year is out.

Just to be clear about the rules for those not familiar with them, the World Superbike Championship allow for production-based bikes with two, three or four cylinders. Three and four-cylinder bikes are restricted to 1,000cc, while bikes with two cylinder engines are limited to 1200cc. Three or four cylinder bikes must weigh at least 165kg, while bikes with two cylinders must weigh 171kg. All teams begin the season with a 50mm diameter air restrictor, and the weights of the bikes and size of the restrictor can be varied if one marque becomes either too dominant or uncompetitive.

Despite getting a leg-up with a larger capacity thanks to its V-twin engine, Ducati's results in World Superbike have been a major factor in establishing the premium Ducati brand of sports bike. It was the first non-Japanese marque for decades to challenge the dominance of the Japanese at their favourite game on the racetrack. All of the Japanese marques are fiercely proud of their racing heritage and have refined the art of building race bikes to the point where they are rarely beaten.

In the premier class of motorcycle racing, the World MotoGP (and previously 500cc Championships), the last non-Japanese bike to win a title was the MV Agusta of Phil Read in 1974 prior to Casey Stoner's win on the Ducati in 2007. That's a third of a century without a non-Japanese win, and it's hard to see a non-Japanese victory again in the near future.

So when the Japanese go racing, you can expect the pace to be hot.

As Superbike, Supersport and now the Superstock 1000 and Superstock racing categories have grown in stature and general recognition, the quest for better results has driven massive focus by the usual suspects (Honda, Yamaha, Suzuki, Kawasaki and Ducati), plus more recently BMW and Aprilia, into building ever more race-oriented roadgoing sports motorcycles upon which to base their factory superbikes.

Along the way, the organisers have attempted to frame a fair set of rules about what can and can't be modified. Hence more and more race special homologation models have been created.

When Aprilia went racing with the RSV4, it was aiming squarely at winning the Superbike title, so much so that it homologated a model where the motor could be repositioned in the frame, all of the steering geometry is variable, and the length and position of the swinging arm can also be changed. Just to ensure the gear ratios of the bike could be instantly tailored to any circuit, Aprilia added a cassette type gearbox to its V4 engine which can be swapped in a few minutes.

Superbike and superstock rules as they are framed, offer a reasonably fair comparison between a standard showroom motorcycle on control road tires and an identical base motorcycle that has been the focus of millions of dollars worth of development (i.e. a factory superbike) in every aspect of the engine and with the added advantage of the best suspension money can buy, plus of course, slick tires, plus a crew of experts in every aspect of a motorcycle's composite parts in attendance at all times.

Then there's the riders to consider – the top ten finishers in any superbike race are world class riders. Superstock riders are very good and getting better all the time as the series becomes recognised as a low-cost feeder league, but superstock riders are not at the same level as World Championship Superbike riders.

The superstock fields have traditionally been comprised of aspiring riders, but they are only part of the way along the journey – you'll see many recognisable names in these classes if you look back through the maze of statistics for each race which can be accessed in the World Superbike Championship site, but long before they were established as leading riders in the foremost categories. Riders in Superstock 1000 are restricted to being under 24 years of age, and riders in Superstock 600 are 20 or younger.

Hence although there is a direct comparison between Superbikes and Superstock 1000 and an identical comparison between Supersport and Superstock 600, there are many factors (tyres, level of support structure and rider quality just to begin with) which indicate that a stock motorcycle would be a lot closer to a superbike in both lap times and top speed if those other factors were also equal.

We had hoped that the fourth round of the 2012 title at Monza last weekend would present us with a perfect set of dry lap times to add to the previous years' lap times and top speeds we had assembled.

Sadly this was not to be, as the whole race three-day event was marred with sporadic rain which denied us a perfect comparison dry-track platform.

Before the event we prepared statistics showing the average best lap times of the top ten finishers in each of the Superbike and Superstock 1000 races held at Monza since 2002 (when Gizmag began), and similarly with the Supersport and Superstock 600 classes which have been running side-by-side since 2006.

We decided to use the top 10 average to ensure that the number we use is an indication of the speed of the overall field, and not just the result of one motorcycle with an excellent tuner.

As most of the sessions for the weekend were marred by rain of some sort, we used the best trap speeds and lap times from any session to arrive at our top ten average for the 2012 Monza round.

Here's what the average top ten lap times each year since 1999 looks like:

The thing I found most fascinating about this view of "motorcycle evolution" was that Superstock motorcycles, which are very representative of the bike on the showroom floor at your local dealership, are now lapping faster, on street tires, than the factory superbikes of just four to five years ago. I think it's safe to assume that any top ten finisher in a World Superbike Championship race has access to factory support and go-fast gear.

Obviously the lap times suffered due to the rain this year, because the average lap time of the top 10 improved 6.3 seconds in the previous eight years (2003-2011).

So the 106.6 second lap time average set by the Superstock 1000 bikes in 2011, on road tires

actually surpasses the top 10 average of the superbikes in 2007, on slick tires with full support crews and factory riders.

The top speed comparison is even more telling, with speeds improving by better than three km/h per year and the average top speed of the top ten Superstock bikes now faster than the Superbike top 10 of 2006.

The equivalent average top ten lap times for the Supersport and Superstock 600 classes run as follows.

and average top ten top speeds showing similar improvement.

What we can see from these charts is that not only are stock motorcycles getting fast very quickly, the speed of the improvement of Superstock machinery appears to be as great, if not greater, than the speed of improvement of superbikes.

The speed of the showroom motorcycles we are now seeing is obviously tending towards the best that the factory can deliver, given the showroom models must pass ever more restrictive noise and emission standards. Indeed, it is hard to conclude anything other than that the range-topping showroom sports bikes are little more than mass-produced racebikes that can be registered for the road.

The engine, suspension and frame components are now being mass manufactured in high quality so efficiently that the amount of money you need to spend to get a small incremental perfromance advantage is now greater than ever – the factories have pushed the race-readiness of the 600cc and 1000cc class to the point where everything can be optimised cost-effectively already has been when it leaves the factory.

Hence to get something substantially lighter, you need exotic materials which cost a lot of money. If you want better suspension, there's a quantum leap in pricing to accompany the low production, high-craftsmanship replacements.

It all boils down to an extraordinary deal for the sports motorcyclist who is getting better and better machinery, with all the trickery that the factory superbikes use getting quickly incorporated into the next model of the road bike.

Now you might argue that it's a chicken-egg argument as to which comes first, but I'm certain that the reason for this extraordinarily rapid evolution of the ability of a road motorcycle to get from point A to point B is all down to the success and visibility of the World Superbike Championships.

I can't wait to see what happens a decade from now when both series of Superstock bikes will no doubt be running with World Championship status and the support structures behind the riders will be more substantial again.

I'm also really keen to see what our readership might be able to see in these figures that I haven't seen.