If you have an aversion to the bitter taste of grapefruit, cabbage, broccoli and even alcohol, you might be a "super-taster," and you're not alone – as many as one in four people have the genetic code that triggers this sensitivity. But scientists have now found that it's also linked to poor health outcomes, including chronic kidney disease and bipolar disorder.

Researchers from the University of Queensland, led by Daniel Hwang from the Institute for Molecular Bioscience, have uncovered a surprising link between those who have two functional copies of the TAS2R38 gene and the likelihood of poor renal function and/or the prevalence of bipolar disorder.

We all have two copies of the bitter-taste gene, one from each parent, but only around 20-25% of the population has both of these as "functional" DNA. And within this group, the researchers identified three tiny mutations – known as single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) – that increased one's chances of being impacted by the kidney and mental health conditions.

“TAS2R38 controls how strongly we taste bitterness in foods such as broccoli and brussels sprouts – making them taste extremely bitter to some people,’’ Hwang said. “If you carry two copies of the gene, you’re highly sensitive to bitter-tasting chemical compounds phenylthiocarbamide and propylthiouracil.’’

These bitter taste receptors (known as TAS2Rs) can be found throughout the body, in the lungs, gut, urinary tract and mouth. There's an evolutionary reason behind why they've been conserved – bitterness is often a key hallmark of poison, so avoiding bitter-tasting food acts as a built-in safety system. And recently, new research uncovered how these bitter taste receptors – of which around 25 different ones have been identified – may actually play a role in healthy aging.

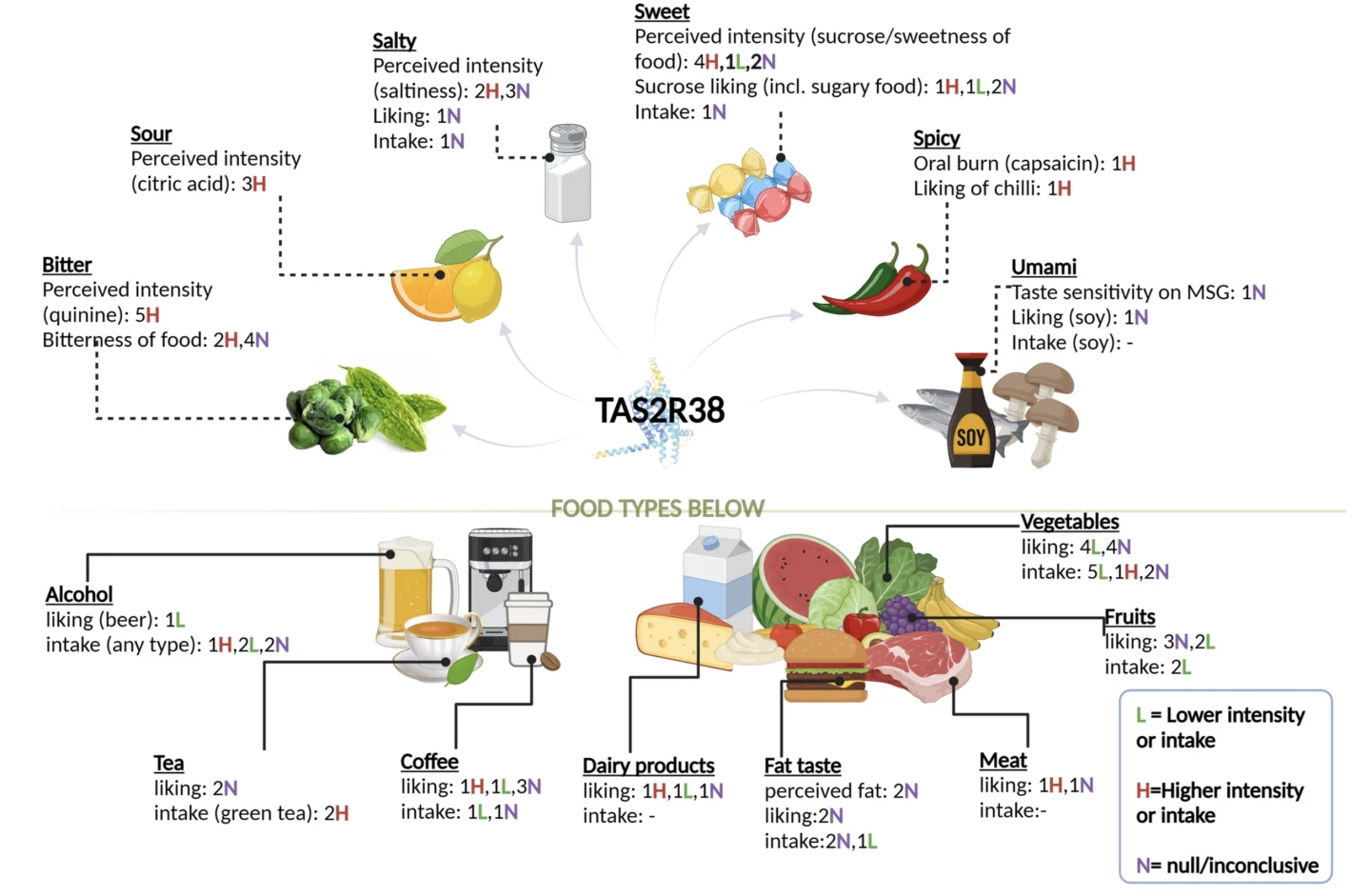

"The TAS2R38 genotype has been linked to the risk of several chronic conditions, such as obesity, cardiometabolic diseases, and colorectal cancer, potentially through its influence on dietary intake," the researchers noted in the study. "TAS2Rs are expressed in extra-oral organs and tissues, including the stomach, kidney, respiratory tract, heart, placenta and brain, suggesting their potential functions other than taste perception."

Investigating this, the researchers focused their work on these three "variants of interest" within functioning pairs of TAS2R38 genes, using a sample size of 445,779 individuals from the UK Biobank aged between 37 and 73, and a further 161,625 people who were part of large-scale genome-wide associations studies (GWAS).

"The strongest association in the phenome-wide exploratory analysis was with bipolar disorder, with the bitter sensitive alleles being associated with a 10% increase in the odds of having this condition in a study of 7,647 cases and 27,303 controls," the researchers noted. "The second strongest association in the exploratory analysis was between the bitter sensitive alleles and higher serum creatinine levels, a biomarker of renal toxicity and poor kidney function. Notably, the bitter sensitive alleles were also nominally associated with chronic kidney diseases and a range of markers of kidney health, including urinary proline betaine levels, glomerular filtration rate, serum non-albumin protein, and glucose levels 2 h after an oral glucose challenge."

The team identified how people with functional TAS2R38 genes generally consumed less alcohol (spirits and red wine, in particular) and foods like grapefruit, and had a higher intake of tea, melon and cucumber in their diet.

“People with the gene are more sensitive to salty tastes – they are less likely to add extra salt because foods are already salty enough,’’ Hwang said. “But interestingly, they enjoy foods that are moderately salty and end up eating more salt overall, which could impact kidney function over time.”

Food choices, based on taste-receptor influences, then impact the makeup of the gut's microbiome – and the researchers found that people with the TAS2R38 gene had a lower incidence of gut problems.

“We found that people with this gene have more Parabacteroides – a type of bacteria that’s actually linked to better gut health and lower inflammation,” said Hwang, who has been studying super-tasters and health for some time.

While the scientists were able to determine this relationship based on what is known about diet and the gut's microbial diversity, less clear is the link between an aversion to bitter foods and the increased risk of bipolar disorder. However, the study has flagged that there may indeed be a strong genetic link here, which could help inform treatment strategies for those with mood disorders.

The study doesn't, however, prove causation – but this link adds to the growing body of evidence that such bitter taste receptors have more complex biological impacts than simply helping hunter-gatherer humans avoid potential plant toxins.

“This information will be useful in designing more personalized nutrition plans,” Hwang said. “While more work is needed, the study provides new research directions for understanding this bitter taster receptor gene in human health."

The study was published in the European Journal of Nutrition.

Source: University of Queensland