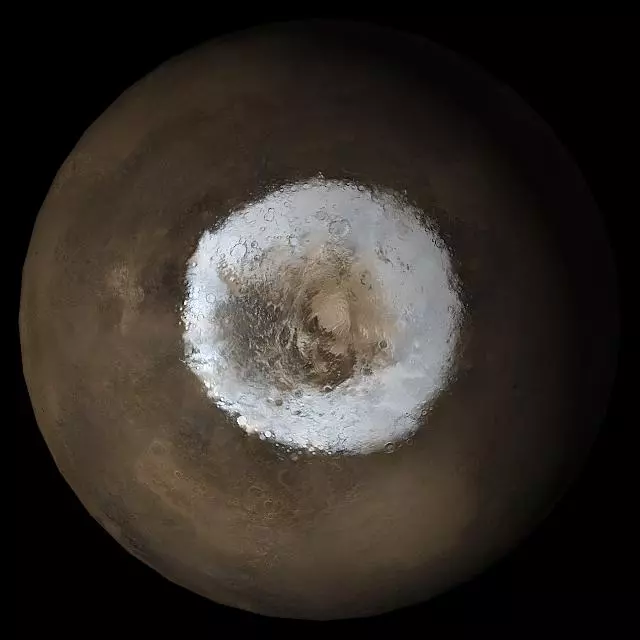

New evidence has emerged in the ongoing debate about whether or not there’s water on Mars. In a study led by the University of Cambridge, scientists examined the topology of Martian ice sheets and found signatures that match subglacial lakes here on Earth.

Evidence abounds to show that Mars was a warm and wet oasis in its distant past, but whether any liquid water remains near the surface today has been less clear. The breakthrough seemingly came in 2018, when radar instruments aboard the Mars Express orbiter revealed bright spots beneath the ice caps at the Red Planet’s south pole, consistent with signatures given off by lakes of liquid water beneath ice sheets in Greenland and Antarctica.

Scientists on that study estimated that the lake sat below 1.5 km (0.9 miles) of solid ice, and stretched about 20 km (12.4 miles) wide. Temperatures there would drop to -68 °C (-90 °F), but the lakes would remain liquid thanks to high salt content and pressure that lowers the freezing point of the water. Another hypothesis suggests that Mars may still be volcanically active, and this geothermal heat could keep the water warm enough to be liquid. Follow-up observations found evidence of several other buried lakes in the area, too.

But the story might not be quite that simple. The debate has been raging over the last few years, with several studies suggesting the bright radar spots could be produced by other things like frozen clays and iron-rich volcanic plains. So for the new study, the researchers investigated the idea with a different line of evidence besides radar.

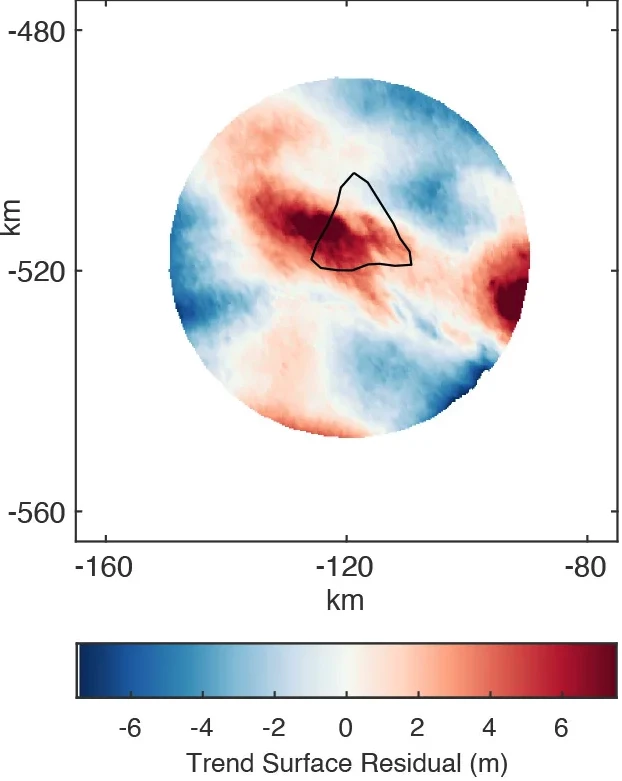

Here on Earth, subglacial lakes can affect the surface of the ice above them in specific ways by lowering the friction between the ice sheet and the rocky bed below. That changes how the ice flows over time, producing a depression in the center and raised mounds downstream.

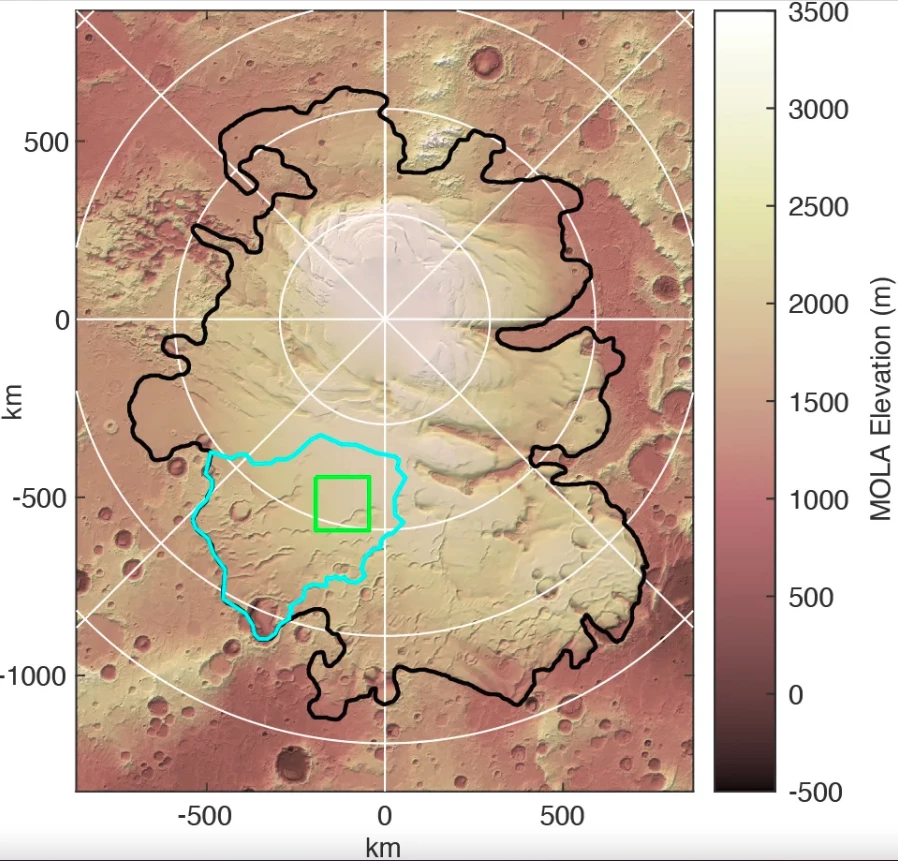

To find out if the Martian ice caps have that sort of structure, the researchers examined data from NASA’s Mars Global Surveyor satellite, which measures the altitude of points on the surface using lasers. And sure enough, they found a large-scale undulation containing both a depression and a raised area, stretching across 10 to 15 km (6.2 to 9.3 miles) with a variance of several meters above and below the surrounding ice.

To back it up, the researchers then ran computer simulations of ice flow under Mars conditions, with various levels of geothermal heat radiating up from below. When a patch of reduced friction, in the form of liquid water, is added to the simulation, the undulations produced are similar in size and shape to those observed on the actual Red Planet.

While the case is far from closed, it is fascinating to find supporting evidence from a completely different source. Even if some of the radar signals are indeed false positives, it’s now a little bit harder to outright dismiss the idea of liquid water on modern Mars.

“The combination of the new topographic evidence, our computer model results, and the radar data make it much more likely that at least one area of subglacial liquid water exists on Mars today, and that Mars must still be geothermally active in order to keep the water beneath the ice cap liquid,” said Professor Neil Arnold, lead researcher on the study.

Further observations from other spacecraft and instruments will help shed more light on the mystery, which could eventually prove to be an important resource for future human missions to Mars.

The research was published in the journal Nature Astronomy.

Source: University of Cambridge