Cancer cells are notorious for evading detection by the body’s immune system, making them difficult to treat. But a promising new type of genetically engineered T-cell that can effectively destroy solid cancer tumors may be just what the doctor ordered.

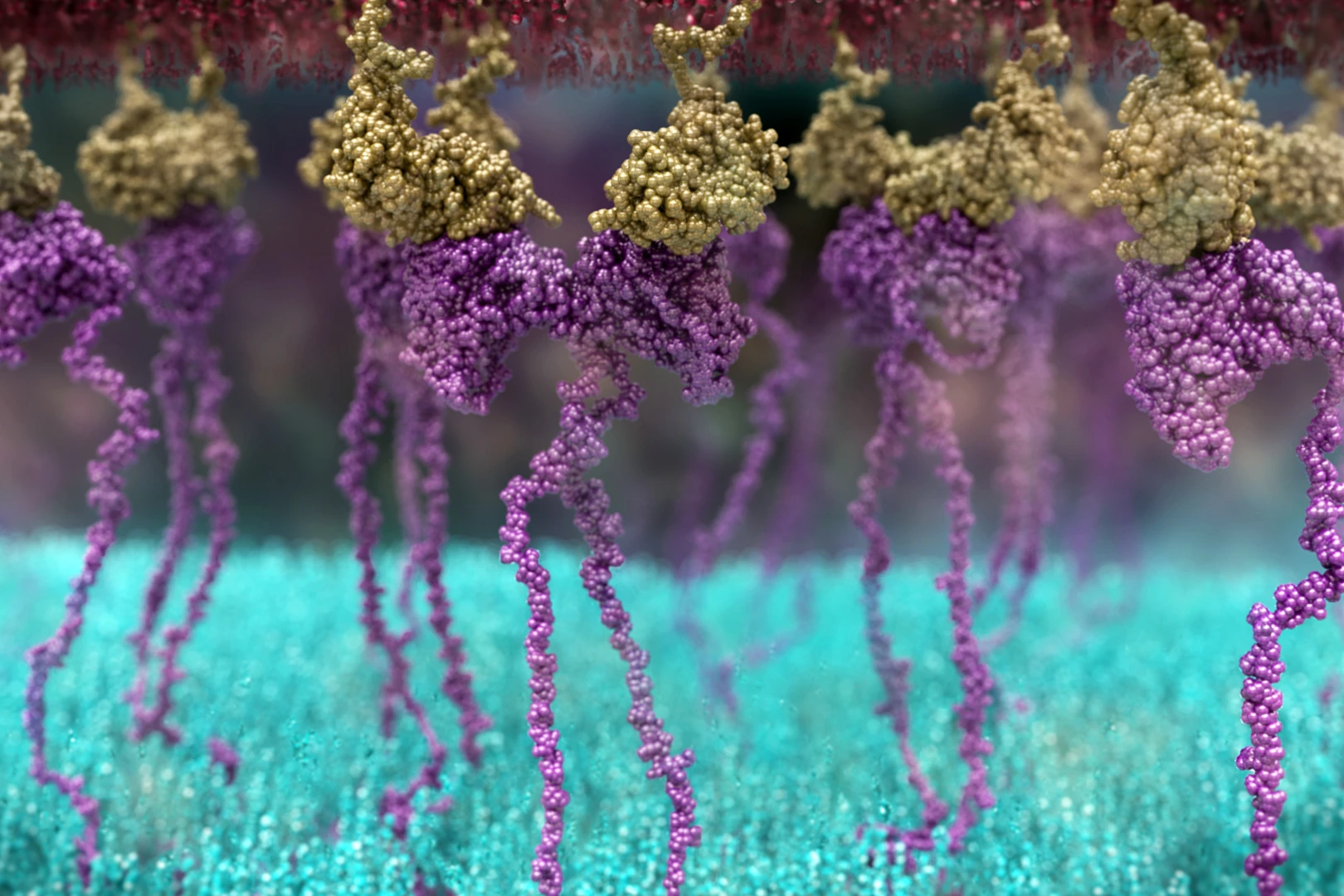

Killer T-cells are an important part of the immune response. They are the body’s security guards, actively patroling for things that don’t belong, such as infections and other diseases. Killer T-cells possess surface receptors that recognize and latch on to foreign invaders and abnormal cells, destroying them.

Cancer cells can evade detection by killer T-cells, making them difficult to destroy. But there is a way our body’s T-cells can be “taught” to recognize and attack cancer cells. One approach is to use chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cells, genetically engineered cells with a new receptor that allows them to bind to and kill cancer cells.

Different cancers have different types of antigens, and each kind of CAR T-cell immunotherapy is designed to fight a specific cancer antigen. CAR T-cells have been used to treat chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) and non-Hodgkin lymphoma, with success rates of 35% to 70% but have been less successful in treating solid cancer tumors.

Now, researchers from the Peter MacCallum Cancer Center in Australia have tested the effectiveness of a new kind of CAR T-cell in treating solid tumors.

“While CAR T-cell therapy has been approved in some types of blood cancers like leukemia, lymphoma and myeloma, the success of CAR T-cells in solid cancers is limited,” said Paul Neeson, a corresponding author of the study. “This is due to factors including poor CAR T-cell expansion, persistence and exhaustion when fighting the tumor.”

Researchers used a younger T-cell, more akin to a stem cell, as an alternative. Called T stem-like CAR T-cells, these cells have an increased ability to reproduce when carrying the CAR receptor and persist in the body for a long time. Testing with the new cells yielded promising results.

“Importantly, these T stem-like CAR T-cells have improved anti-tumor function in the culture dish and in four pre-clinical models. In fact, they completely eradicated pre-existing solid tumors when combined with the immune checkpoint drug, anti-PD-1,” Neeson said.

To distinguish normal cells from foreign ones, the immune system uses “checkpoint” proteins on immune cells that act like switches that have to be turned on or off to start the immune response. Monoclonal antibody medications can be designed to target these checkpoint proteins, and although they don’t kill cancer cells directly, they help the immune system better attack the cancer cells.

PD-1 is a checkpoint protein on T-cells that acts as an off-switch, stopping T-cells from attacking other cells in the body. Monoclonal antibodies that target PD-1 can block this binding (hence, anti-PD-1), boosting the body’s immune response against cancer cells.

The researchers could generate fully functional T stem-like CAR T-cells in six days instead of the standard 14 days, making the procedure both cost-effective and scalable.

They hope to trial the next-generation CAR T-cells in clinical trials on pediatric patients with difficult-to-treat blood cancer before treating other types of cancer.

“We would aim to use these cells in two pediatric leukemias that are resistant to treatment," Neeson said. "We believe our protocol will harmonize the CAR T-cell product to one that has consistent anti-tumor function and the important ability to persist. Once we show these cells are safe, we will turn our attention to developing this treatment for pediatric solid cancers, including osteosarcoma and neuroblastoma.”

Osteosarcoma (osteogenic sarcoma) is a type of bone cancer often seen in the long bones of the arms and legs. It’s common in teenagers and young adults. Neuroblastoma starts in immature nerve cells (neuroblasts) and can develop in different body areas. It occurs most often in infants and children under the age of five.

The below video by the Peter MacCallum Cancer Center explains how T-cells work as part of the body’s immune response and how CAR T-cells are produced.

The study was published in Science Translational Medicine.

Source: Peter MacCallum Cancer Center