Immunotherapy is a promising avenue for cancer treatment, but it has trouble against solid tumors without triggering major side effects. Now, researchers at McMaster University have developed a new form of the treatment that supercharges a different type of immune cell.

The human immune system is our most effective defense against disease, but it’s not infallible. Cancer is particularly crafty, using a range of tricks to avoid detection and fight off immune cells that come knocking.

Immunotherapy aims to swing the odds back in our favor. The most common form of the treatment is called chimeric antigen receptor T-cell (CAR T cell) therapy, where doctors extract T cells from the patient, engineer them to target cancer proteins, then return them to the body. Once there, they can launch a more effective attack.

So far, the technique has worked well on some forms of leukemia, but not so great against solid tumors. That’s because those cancers produce a strong environment around themselves that exhausts T cells quickly, or make it difficult for them to target the cancer. Other times the souped-up T cells can proliferate out of control, leading to a potentially fatal immune condition called a cytokine storm.

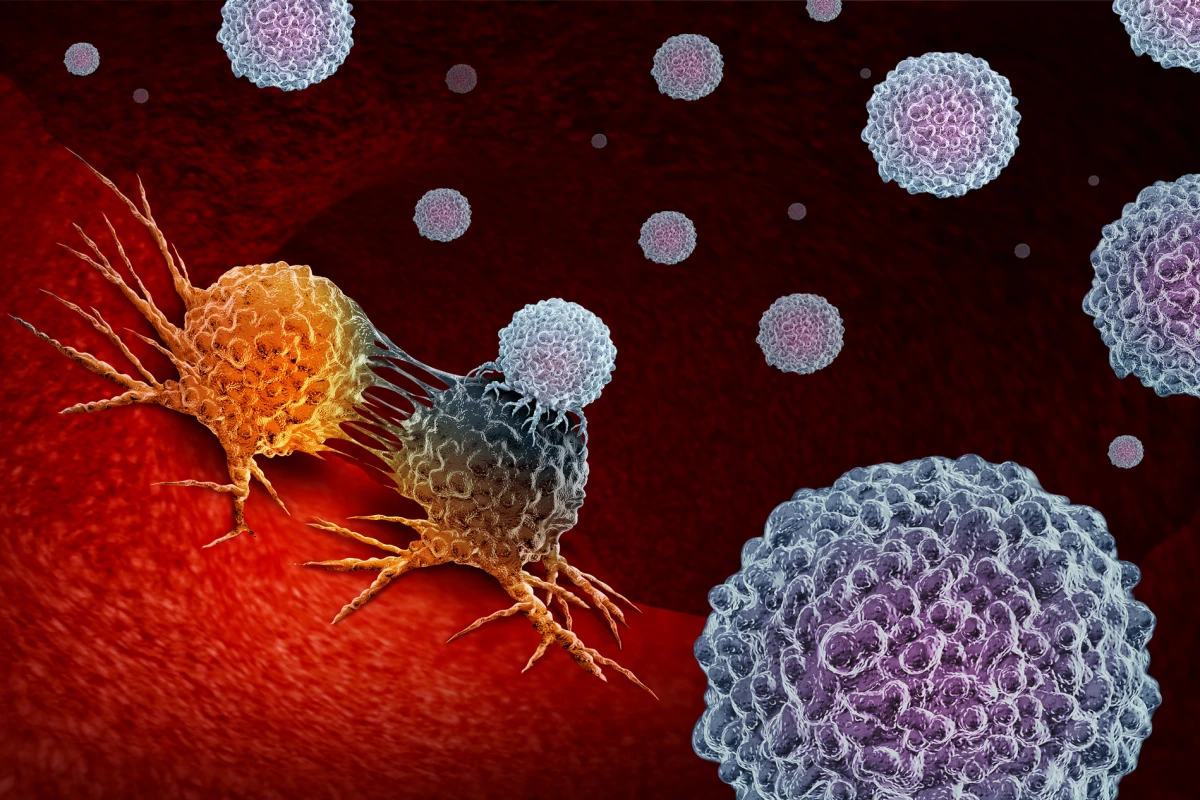

So for the new study, the McMaster scientists investigated alternatives to CAR T cell therapy. Rather than removing and editing T cells, they used a different type of immune cell called natural killer (NK) cells, which the team says should be more selective in targeting only cancer.

"These CAR-NK cells are a little bit smarter, in a way, in that they only kill the enemy cells and not good cells that happen to have the same marker," says Ali Ashkar, corresponding author of the study. "These cells have a sober second thought that says, 'I recognize this target, but is this target part of a healthy cell or a cancer cell?' They are able to leave the healthy cells alone and kill the cancer cells.”

To test it out, the researchers took NK cells from patients with breast cancer, engineered them to target receptors found on cancer cells, and introduced them to tumor cells derived from the patients. They found that CAR-NK cells were able to kill more cancer cells than CAR T cells tested in the same way, even in the presence of the suppressive environment that solid tumors build around themselves.

But perhaps most importantly, the CAR-NK cells did not kill healthy cells in the samples – even those that expressed the same protein that the therapy was targeting on the cancer cells. Altogether, the study could open up new therapy options for hard-to-treat solid cancers.

"We want to be able to attack these malignancies that have been so resistant to other treatments," says Ana Portillo, lead author of the study. "The efficacy we see with CAR-NK cells in the laboratory is very promising and seeing that this technology is feasible is very important. Now, we have much better and safer options for solid tumors.”

Of course, it is very early days for this work – so far it’s only been tested in the lab – and animal tests will need to be conducted before we even think about humans.

The research was published in the journal iScience.

Source: McMaster University